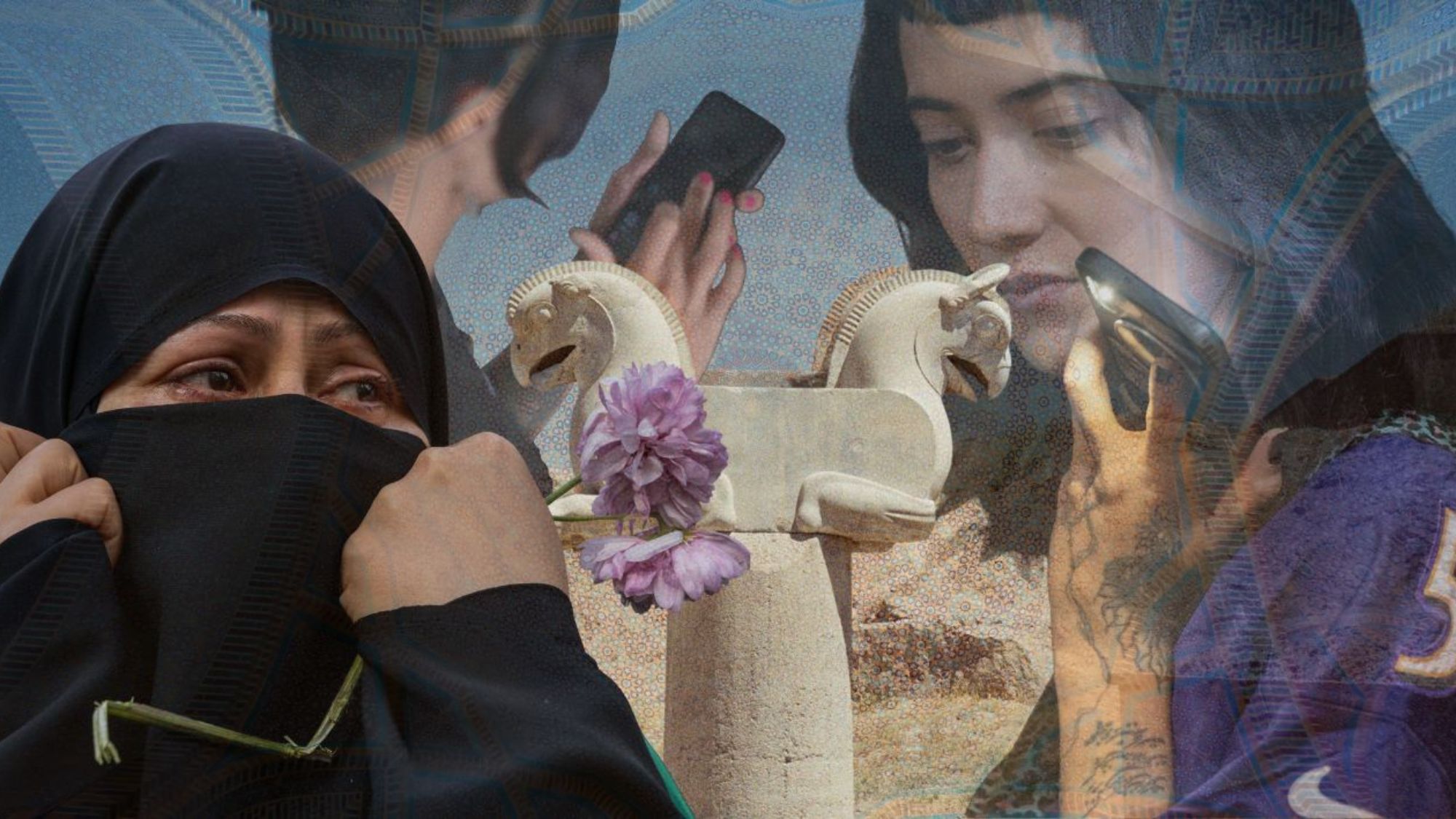

Iranian Women in Exile Share Their Stories of Life Between Two Worlds

Thousands of miles from home, Iranian women in exile live tethered to Iran through notifications, blackouts, and unanswered calls.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Tara Aghdashloo, an Iranian writer and director, has been awake since 3:45 a.m. when we speak. This is not unusual for her; sleeping has become increasingly rare since widespread protests erupted across Iran in response to catastrophic economic collapse and what many see as Iran's repressive regime.

She is constantly online, receiving messages at all hours and exposed to multiple news sources. Sleep comes in fragments. An activist and former journalist, she shares updates about escalating protests and the regime’s crackdown against demonstrators, tries to respond to as many people as she can, and then attempts — often unsuccessfully — to rest.

By the time we speak at midday, Tara has been awake for over seven hours. She’s already heard from a friend who says their cousin — or perhaps a friend of a friend, the details blur as one trauma bleeds into another — was allegedly beaten to death along with a sibling in Isfahan in front of their mother. Isfahan, a historic city so rich in beauty and culture that it earned the name “Half of the World,” is visually at odds with the brutality tearing through its streets. It is just shy of 5,000 km from London, where Tara has lived for many years, but like many Iranians, she feels the distance between her current home and her native land dissolve.

Iranians’ phones have become conduits of grief, outrage, fear, and hope.

“What’s happening in Iran affects me deeply in my day-to-day life,” says *Yasmin, a 20-something British-Iranian PR executive living in London who goes by an alias for fear of reprisal. “I feel an unbreakable emotional connection to the country.”

Like Tara and Yasmin, Mouna Esmaeilzadeh, an Iranian doctor and entrepreneur now based in Sweden, also struggles with the constant and unrelenting weight of digital fear. Each notification, message, or news alert carries both the hope of connection — the long-awaited confirmation that their loved ones are safe — and the fear of the worst. Iranians’ phones have become conduits of grief, outrage, fear, and hope.

“We live in a constant state of emotional whiplash; on a roller coaster thrown between hope and despair,” adds Mouna. As a neuroscientist, she is acutely aware that her brain — like countless others’ (current estimates put the Iranian diaspora at 4–5 million) — is running on overdrive. Normally, she would limit her social media exposure, but these are not normal times. She says she feels compelled to watch and share the brutal realities unfolding before her eyes.

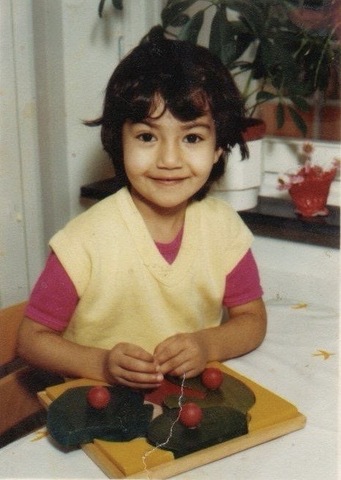

Mouna Esmaeilzadeh was born in Iran in 1980, and fled to Sweden at the age of three. Barely surviving the dramatic journey as refugee.

“Every time I open a social media app, I’m confronted with images and videos coming out of Iran. I would never try to keep it separate — it’s part of my identity. When I know that people there are suffering, it hurts me as well,” is how *Roxana, a 39-year-old creative living in Austria, puts it.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Arghavan Salles, a surgeon, Stanford professor, and leading advocate for gender equity and diversity, also carries immense guilt daily. “Seeing videos of doctors saying they need help, that they need more specialists, makes me want to go there immediately. But because of the activism I’ve done in the past, particularly for the Woman, Life, Freedom movement that started in 2022, I would likely be imprisoned as soon as I arrived.”

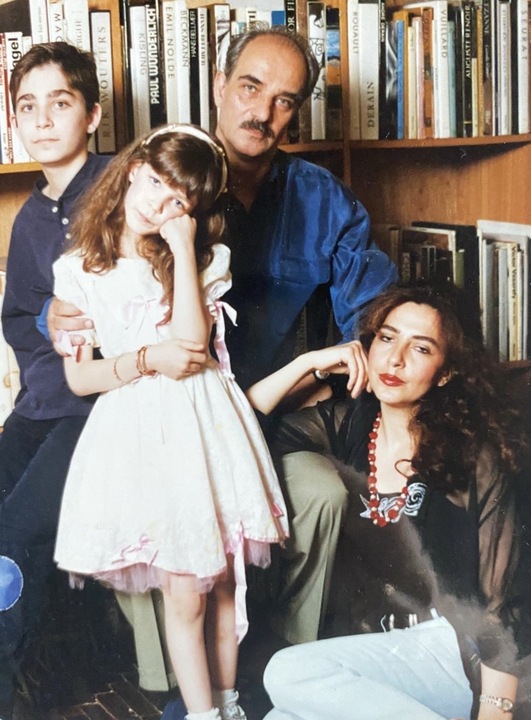

Tara, who moved to Canada with her family in the early 2000s — most of whom are currently in Iran — also lives in exile. She hasn’t seen her grandmother since 2022, and hasn’t had any contact with her mum in over a week since the blackouts. She tries to remind herself that whenever she would speak to her family during the 12 Day War, they would be together, piecing together a jigsaw puzzle. “People in Iran are so strong,” she tells me. It’s a sentiment that has been repeated to me many times in different ways, but with the same message: we are resilient people — loving, humorous, and community-minded — even as surveillance and oppression try to drive us apart. Tara’s hope that her family is “doing beautiful things together right now to keep each other company” offers light relief.

Tara Aghdashloo with her family in Iran before the moved to Canada.

Another source — who wouldn’t share their name — was able to speak to their mother for the first time since the blackout, thanks to a stranger online whose relative in Iran has internet access. “Phone to phone, we spoke, and I heard her voice. I was crying, not wanting her to know I’m crying, and she’s trying to tell me that everything is fine.”

For the Iranian diaspora, the fear and uncertainty they carry are intensified by the digital repression happening at home. As Bahar Ghandehari, Director of Advocacy at the Center for Human Rights in Iran, explains, “For many Iranians, especially the youth who have grown up in a digital age, online spaces are a primary means of self-expression and connection to the outside world, exposing them to freedoms and rights denied at home.” Yet those same spaces are tightly monitored, explains Ghandehari: women who sing, dance, or share content without the mandatory hijab, and ordinary citizens who criticise the state online, risk arrest, account closures, and fines. She warns that authorities have also rolled out a “national internet” that isolates Iranians from the wider web, while AI-driven surveillance and facial recognition are increasingly used to identify protesters. For diaspora women, these blackouts and digital crackdowns create a constant, looming uncertainty. Each disrupted call or message is a reminder of their loved ones’ vulnerability and the limits on freedom they cannot escape.

Even outside Iran, the pressures don’t stop. Many British-Iranians say they feel compelled to self-censor, questioning what they post, share, and like online. “Safety is always a consideration,” says *Yasmin, who has a private Instagram and regularly “sweeps” her account to remove unfamiliar profiles, “in case they are connected to the regime.” Despite the risks, she says she cannot bear to stay silent. “There is a line by the Persian poet Saadi that feels especially relevant right now. In English, it translates to: ‘If you have no sympathy for human pain, the name of human you cannot retain.’”

A photograph from *Roxana's last trip to Iran in 2024.

Self-censoring begins at an early age for Iranian girls. Tara, although she was only a primary school student during the early days after the war, remembers teachers trying to trip children up by asking questions like, “Does anyone’s parents have alcohol at home?” Like *Roxana, she grew up knowing that certain conversations weren’t to be repeated. “Even in London, sometimes when we’re at a restaurant, and I hear someone speak Persian, my immediate gut reaction is, ‘Oh my God, did I say something that I shouldn't have said?’”

Social media, once a lifeline to culture, community, and protest, can become a source of anxiety as diaspora women navigate the fine line between expressing solidarity and exposing themselves to surveillance or backlash. For many, this constant calculation adds a heavy layer to everyday life, shaping how they speak, share, and move through spaces, both online and offline.

Many of the people doing a lot of the heavy lifting to educate and raise awareness of what’s happening in Iran are women. That is an immense burden.

Arghavan Salles

“There is a physicality to it,” explains Tara. “You take your body out into the normal world here, you go to the bakery, and someone’s just chatting on the phone. It feels surreal. Sometimes I get resentful. I think, how could you not care about this? Or why isn’t everyone shouting and crying? Of course, they shouldn’t be — they have their lives — but you still become really angry. This week, I’ve just been so angry. I’m angry at everyone.”

She finds herself angry at friends, too, the non-Iranian ones, who try to empathise but get the politics wrong. The helplessness of the situation makes even small conversations with loved ones feel urgent. Convincing or informing just one person can feel like the only way to make a difference in a day. “I was a professional journalist, and I find myself in the comments section of some fucking page arguing at 3 in the morning with an ‘angel XO85’ from Arizona about fascism,” says Tara, aware that what keeps her scrolling, arguing, and posting is the urgent need to set the record straight and share the reality of Iran with those who have never lived it. “I feel a personal responsibility to do whatever I can to make sure the truth is seen and understood,” agrees *Yasmin.

Tara understands why many British-Iranians don’t call out the regime the way she does, but because of her background, language skills, and education — as well as her deep ties and love for her home country — she feels it is her duty to speak up. “It’s the least I can do, but it's at a very high cost.” Arghavan points out that many of the prominent voices in the Iranian diaspora are women. “Meaning many of the people doing a lot of the heavy lifting to educate the public and raise awareness of what’s happening in Iran are women.” That, she explains, is an immense burden. “To not only have to be informed about what is happening, but to articulate it in a way that is easily understandable and actually serves the people of Iran.” She describes the tension between wanting and needing to bear witness while avoiding overwhelm as “a massive psychological toll,” though she’s quick to add that this struggle pales in comparison to the challenges faced by those living in Iran.

Before going back to Iran the summer before last, *Roxana deleted all her posts critical of the regime, fearing she might be denied entry — or worse. But this, she says, is too important an issue to remain silent about, even though she hopes to return one day. “Maybe at that point I won’t have to worry anymore, because I’m returning to a free Iran,” she wonders. Arghavan shares the same hope; she says she’s unsure whether it will be in 2026 or years later, but she knows the people of Iran will be free. “And when that happens, we will have the biggest and best mehmoonies anyone has ever seen.”

Mischa Anouk Smith is the News and Features Editor of Marie Claire UK, commissioning and writing in-depth features on culture, politics, and issues that shape women’s lives. Her work blends sharp cultural insight with rigorous reporting, from pop culture and technology to fertility, work, and relationships. Mischa’s investigations have earned awards and led to appearances on BBC Politics Live and Woman’s Hour. For her investigation into rape culture in primary schools, she was shortlisted for an End Violence Against Women award. She previously wrote for Refinery29, Stylist, Dazed, and Far Out.