Kim Kardashian’s ‘Back to School’ Skims Drop Shows We’ve Still Got a Sexy Schoolgirl Problem

Can we stop dressing up girlhood for the male gaze already?

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It’s time for media, fashion, and social platforms to stop turning the image of the schoolgirl into something ripe for adult consumption.

It seems strange to have to point this out, but given the cultural climate, it bears repeating: a girl in a school uniform is just that — a girl in a school uniform. She is not “jailbait.” She is not “asking for it.” She is not a nostalgic fantasy, a marketing opportunity, or a Halloween costume.

And yet, the sexualised schoolgirl remains one of pop culture’s most enduring tropes. Across film and fashion, music and social media, the aesthetic of adolescence is constantly polished and repackaged for adult appeal.

Britney Spears was just 17 when she wore that now-iconic school uniform in Baby One More Time, but the image has endured for decades, serving as both a pop legend and a cultural warning sign.

More recently, Kim Kardashian — ever attuned to a lucrative marketing moment — launched the new Skims Campus collection ahead of the “back to school” season. Think flannel pyjama pants, baby tees, tube socks, pom-poms, “novelty accessories,” and plenty of plaid. These are classic collegiate hallmarks, styled on what Skims exclaims are “real college students!” But the visual language of tiny shorts, cheerleader energy, and soft-focus sleepover vibes clearly suggests something more than cosy loungewear.

Kim Kardshian's SKIMS 'Back to School' Campus collection

As a ’90s kid, I’m hardwired to respond to the aesthetic. It reminds me of the teen flicks we played at sleepovers: Jawbreaker, She’s All That, even Not Another Teen Movie — basically any film featuring Solo cups and 25-year-olds playing badly behaved teenagers. Today, it’s actual 18–21-year-olds fronting ad campaigns built on decades of male-gaze fantasy.

The Skims Campus collection — like the brand’s viral face wraps — will no doubt sell out. And to be clear: Kim Kardashian alone isn’t the problem. She’s a product of this system too. But when we continue to sexualise schoolgirls, we contribute to a culture that endangers them.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Why, in 2025, are we still so invested in dressing up adolescence for adult attention? Why, more than 70 years after Nabokov unleashed Lolita on the world, are we still so culturally obsessed with sexualising schoolgirls?

Hannah Nixon, a writer whose play LOLA explores similar themes, notes the dissonance between the book and the widespread social understanding of the relationship between Lolita and her abuser-stepfather Humbert Humbert: “She’s a child being sexually abused by her stepfather, and so it’s very indicative of society that the narrative of what happens to her has been turned on its head and turned into something that is about a teenage child — actually, she’s not even a teenager — having some sort of power sexually over a man.”

Evocative of Adrian Lyne’s 1997 adaptation of Lolita, a young, blonde Skims model is shown blowing bubblegum in a baby pink tube top and hot pants — the outfit also brings to mind early Britney or Christina Aguilera. Elsewhere in the campaign, another familiar porn trope appears: the “sexy secretary.” A young girl in thin-rimmed glasses poses with a pencil pursed between her lips, gazing seductively into the camera. This isn’t just playful branding — it’s a well-worn formula: stylised, infantilised, sexualised.

The sexualised schoolgirl has long been a fixture in the porn industry, too. “Teen” is the most-searched category on major porn platforms, and its impact is far-reaching. Research suggests that “barely legal” porn, while technically featuring adults, functions much like virtual depictions of minors by activating “youth‑focused sexual schemas,” which, over time, may contribute to emotional desensitisation and escalation to content that is more extreme or deviant.

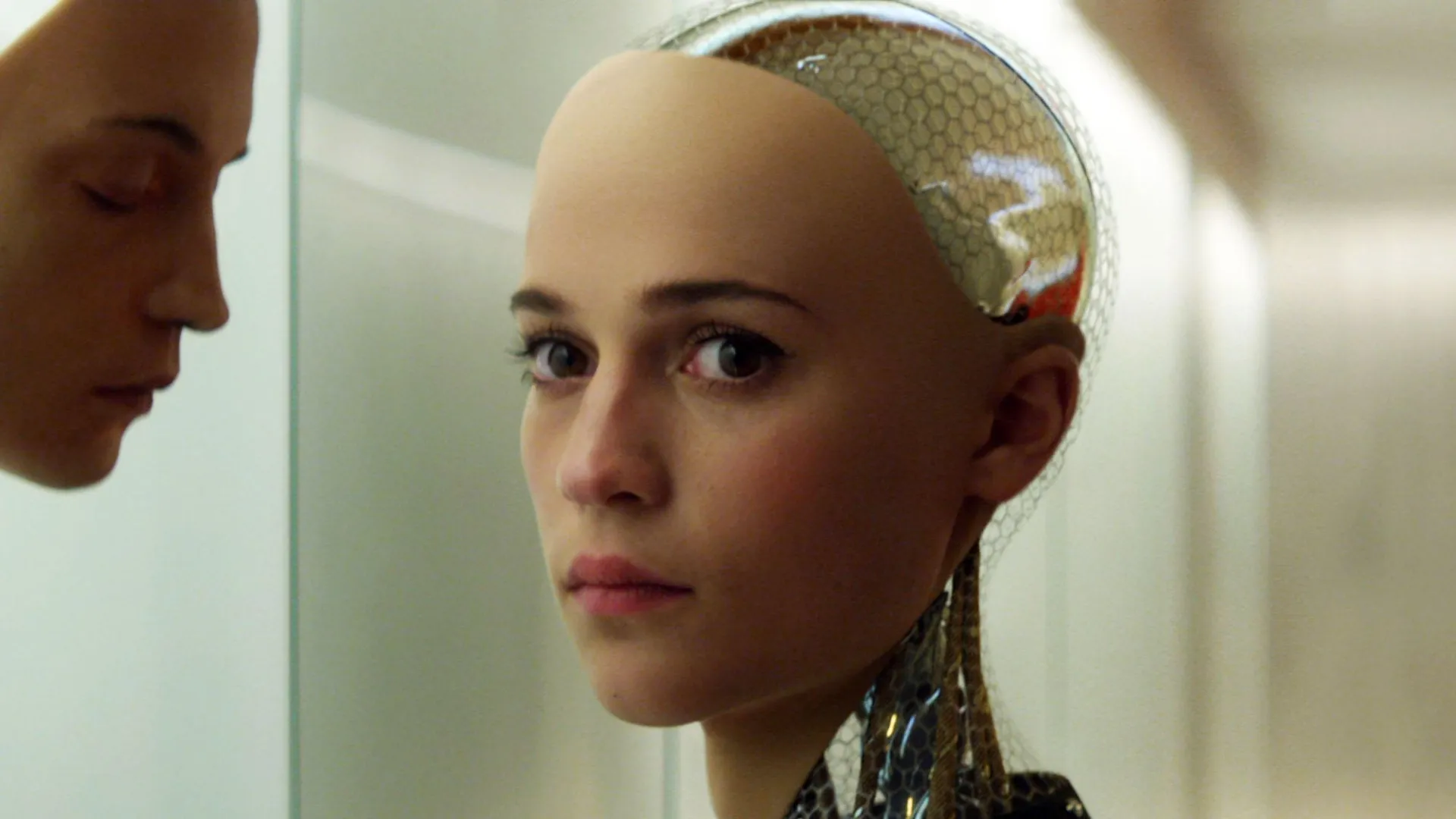

Now, with the rise of AI-generated “schoolgirl” content, that exploitation is colliding with technology in terrifying new ways. Studies indicate the surge in AI-generated “barely legal” content can normalise and reinforce the sexual interest in minors, according to research by the National Library of Medicine.

Then there’s the world of online sex work, where the influencer economy meets pornography.

In the much-discussed documentary 1,000 Men and Me: The Bonnie Blue Story, the OnlyFans creator details her “Schoolies” strategy: showing up at Australia’s end-of-high-school party week and distributing business cards with QR codes to her account. She later toured university Freshers’ Weeks around the world, seeking out “barely legal” young men to film sex acts with.

More recently — and more disturbingly — Blue filmed a so-called “sex education” class, using visibly young-looking OnlyFans hopefuls dressed in school uniforms. As reported in the documentary, these young women — and young men — weren’t paid, but participated in hopes that Blue’s fame would boost their visibility and, in turn, their earnings. The classroom setting and uniforms weren’t just a backdrop — they were the entire product. They also serve to reinforce the damaging idea that schoolchildren, or any child for that matter, can somehow be complicit in their abuse.

A post shared by Y2KDAILY by T. (@y2kdaily)

A photo posted by on

In defending her content, Blue made a chilling point in an interview with Janice Turner for The Times: “Men have made porn content with schoolgirls since day one... no one has ever caused an uproar about that. So why can’t I do a schoolboy?”

It’s true that the cultural obsession with “barely legal” girls has rarely been met with sustained outrage. But that doesn’t mean it’s harmless. A concerning Harvard study showed that after prolonged exposure to pornography, viewers perceived rape as less serious, endorsed shorter prison terms for offenders, showed less empathy for victims, and developed greater sexual callousness toward women — even in scenarios involving minors.

When we glamourise schoolgirl imagery, whether in porn, fashion, or influencer content, we feed a system that trains girls to see themselves through the eyes of adults. We make them more vulnerable to grooming and harassment, and to self-objectification at younger and younger ages. We teach them that their value lies in their desirability.

Just this week, Lil Tay — the “Youngest Girl On OnlyFans” — claimed she made $3M in just three hours on the site mere hours into her 18th birthday. In the run-up to her milestone birthday, Lil Tay began promoting the fact she would be releasing the “youngest link of the century” (OnlyFans bans under-18s on the platform), with an “18th Birthday Countdown.” At 12:01, she began filming content and claims to have made $1M within three hours.

Kim Kardashian's SKIMS 'Back to School' Campus collection

Dr Charlotte Ord, a psychologist and author of Body Confident You, Body Confident Kid, a guidebook for helping parents teach their children to develop a positive body image, is concerned about the impact of young viewers in the current media landscape. “Exposure to sexualising material at a young age, whether adult film or physical intimacy itself, would interrupt healthy psychosexual development in that way.” Ord says she is worried that viewers, particularly younger viewers, “might think that they have to emulate that kind of behaviour in order to get attention, to get on in life, or at the very least become completely desensitised [to] very extreme sexual behaviours.”

It’s a concern shared by the UK pornography taskforce, which has proposed banning “barely legal” content after Channel 4’s Bonnie Blue documentary. The show has reportedly accelerated the taskforce’s work and prompted calls for legislative change, aiming to close legal loopholes around “barely legal” themes and limit the normalisation of youth eroticisation both online and offline.

The UK government’s new Online Safety Act and emerging initiatives also signal a shift. As Ofcom prepares to enforce age-verification rules and restrict sexualised content that fetishises youthful aesthetics, we might finally be seeing a turning point in how our society defines protection versus permissiveness. It is long overdue.

When teenagers absorb the idea that being watched, desired, and consumed is part of coming of age, their self-worth becomes tethered to sexual validation. Glamourising the schoolgirl trope is not just playing dress-up, it has real-world consequences. It’s time to end the Lolita fantasy once and for all.

Mischa Anouk Smith is the News and Features Editor of Marie Claire UK.

From personal essays to purpose-driven stories, reported studies, and interviews with celebrities like Rosie Huntington-Whiteley and designers including Dries Van Noten, Mischa has been featured in publications such as Refinery29, Stylist and Dazed. Her work explores what it means to be a woman today and sits at the intersection of culture and style. In the spirit of eclecticism, she has also written about NFTs, mental health and the rise of AI bands.