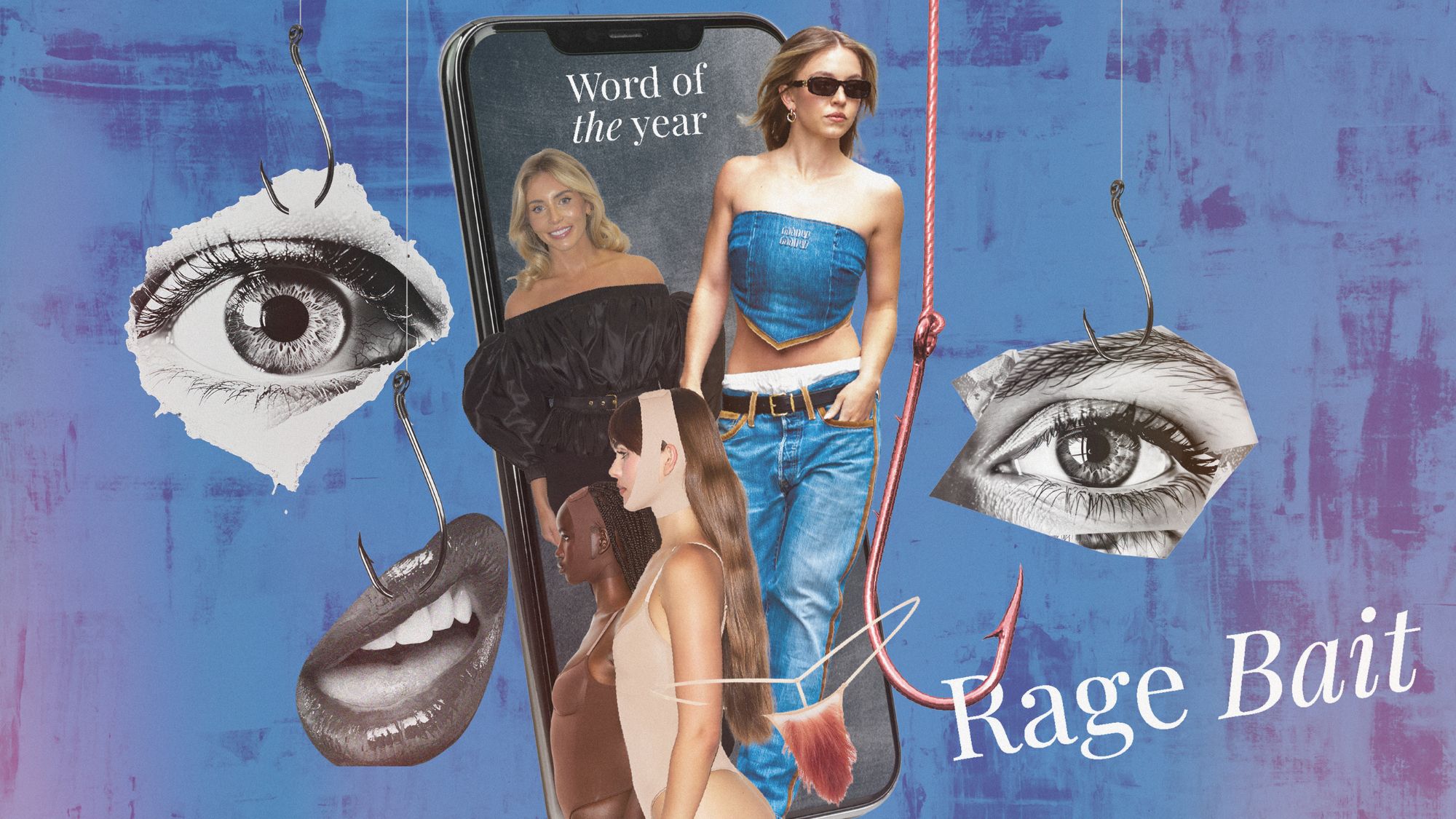

Rage Bait Isn’t the Word of the Year We Want, But It’s the One We Deserve

From the Kardashians to Sydney Sweeney, Oxford’s 2025 word of the year explains why the internet is driving us all mad

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In a move that is almost embarrassingly 2025, the Oxford English Dictionary has declared ‘rage bait’ its word of the year. We could have had, oh, I don’t know, ‘hope’, or ‘repair’, but no — we got rage bait, a term that captures the emotional manipulation underpinning modern life and is, as such, perfectly fitting for being crowned “word of the year.”

So, what is rage bait?

At its simplest, rage bait describes the kind of content increasingly filling your feeds — the sort that seems deliberately designed to spark outrage: Kim Kardashian’s face shapewear, say (see also: the provocative campus collection, pube thongs, nipple bras… you get the picture), or that Sydney Sweeney ad. Posts that are so inflammatory that they spread like wildfire before you’ve even had time to question their validity fall under the category of rage bait. AI slop (surely a contender for next year’s Oxford Word of the Year) feels rage bait-adjacent, too.

Communication scholar Angèle Christin describes rage bait as “the negative, vengeful cousin of clickbait.” She adds that whereas traditional clickbait tries to spark curiosity (“You’ll never believe what happened next!”), rage bait goes further — “it engages negative emotions, often provoking you to make harsh comments.” You only need to open your social media app of choice to see this in practice.

SKIMS' viral 'Ultimate bra' caused a social media storm when it launched earlier this year

And yet, you’d be forgiven for wondering why anyone would want to actively incite such fury. The answer lies in the power that rage bait gives its creators. Take Donald Trump, for example, a man famously unafraid of controversy. Earlier this year, I started a roll call of everything he had done since becoming president — ending DEI programmes, stating only two genders should be recognised: male and female, and expressing unwavering support for the death penalty, to name but a few — but ultimately found that tracking executive orders was a full-time job in itself. And yet I couldn’t help myself from obsessively following the updates and inevitably heading to the comments after just to really wind myself up.

Academics call this the confrontation effect: when users engage more with ideology-inconsistent content online than with content the agree with. A study published in Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes found that people (like me, and perhaps you?) are more likely to interact with political posts that challenge their views rather than align with them. Reporting on the phenomenon of rage bait, the authors write: “Individuals are strongly driven to voice their outrage toward those with whom they disagree.”

Divisive figures both depend on and benefit from media structures that magnify outrage and reinforce group-specific worldviews.

It’s not just politicians who can rile up the masses. In fact, 2025 has seen its fair share of rage-baiters across the political and cultural spectrum. The extended Kar-Jenner clan have long peddled in rage bait-y behaviour. Weighing in on SKIMS’ “The Ultimate Bush” thong hoopla, social scholar MJ Corey of the Instagram account @kardashian_kolloquium and author of the upcoming Dekonstructing the Kardashians: A New Media Manifesto dubbed the affair a way to “stir up a little light, campy body-humour controversy.” Corey also notes — in reference to another Kar-Jenner maelstrom — that “the influencer economy has completely revolutionized media and pop culture, and people with big followings who have made themselves famous for being #viral hold more cultural power than many people want to admit.”

A post shared by @kardashian_kolloquium

A photo posted by on

That desire to go viral above all else can act as rage bait’s catalyst. In the ever-more competitive fight for eyeballs, we’re seeing creators embark on increasingly provocative stunts to boost engagement. Take adult entertainer Bonnie Blue, for example. Her appeal fits the same psychological patterns identified in research on divisive public figures: she uses highly polarising, identity-charged messaging that creates a strong in-group of supporters who interpret her bluntness as authenticity. Her style also mirrors what studies describe as “outrage-based influence”: direct, confrontational communication that thrives in algorithmic environments. In today’s media landscape (especially on social platforms), controversial and emotionally charged content (like having sex with 1,000 men in 12 hours) is amplified because it drives engagement: shares, comments, reactions. Neutral or nuanced discussion often doesn’t. This phenomenon has been described as part of the Outrage Industrial Complex.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

In short, divisive figures both depend on and benefit from media structures that magnify outrage and reinforce group-specific worldviews. And still, even against that backdrop, the fact that “rage bait” has risen to the top of our collective vocabulary hints at a deeper societal question: in 2025, are we expecting to be manipulated — and, moreover, are we too obliging?

We know by now that outrage is profitable: it keeps us clicking, commenting, spiralling, and — most importantly — returning. Social media’s attention economy has evolved into a finely tuned machine that rewards spectacle over substance. Rage bait becoming ubiquitous reflects this shift: we are naming the tools being used on us — and yet (and yet) still falling for them.

The word of the year isn’t just a lighthearted commentary on the internet’s worst impulses; it marks the point where provoking hatred has become a mainstream content strategy. And when outrage becomes part and parcel of our daily digital consumption, the emotional baseline changes. Cynicism becomes instinctive, compassion fatigue sets in, and public discourse hardens into an ongoing, tiresome battle.

But constant outrage has a dulling effect. It makes real issues like climate change, inequality, and democratic backsliding harder to distinguish from made up ones. Anger being turned into entertainment gives us a glow of self-righteousness, a sense of belonging to the “right” side. It also allows us to perform morality instead of practising it. We can see this in the way so many of us are not only exhausted but disengaged, and yet (again, and yet!) somehow more reactive than ever.

Acknowledging rage bait feels like a sad recognition that we’re being manipulated — by politicians, creators, media outlets, and often by one another. But this realisation also, in a way, feels oddly hopeful: the more aware we become of rage bait, the less effective it becomes.

I can’t help but think of the sayings my family cycled through when I was getting bullied at school, things like “Rise above it” and “Ignore them and they’ll get bored.” Except now the bullies are billionaire tech bros bumping rage bait to the top of our feeds to piss us off and keep us on the platforms longer. The sayings are still as unsatisfying as I remember (“What do you mean ‘words will never hurt me’? Of course words hurt,” I find my inner child yelling), but maybe mother’s wisdom prevails. Maybe, for the sake of our own sanity, the best thing we can do is resist the temptation to engage in rage bait. We might not be able to control the algorithms or the opportunists who thrive on inflaming tensions. But we can control our own participation in the cycle; we don’t have to take the bait.

Mischa Anouk Smith is the News and Features Editor of Marie Claire UK, commissioning and writing in-depth features on culture, politics, and issues that shape women’s lives. Her work blends sharp cultural insight with rigorous reporting, from pop culture and technology to fertility, work, and relationships. Mischa’s investigations have earned awards and led to appearances on BBC Politics Live and Woman’s Hour. For her investigation into rape culture in primary schools, she was shortlisted for an End Violence Against Women award. She previously wrote for Refinery29, Stylist, Dazed, and Far Out.