Shades Of Scarlett: We Look Back At The Life Of The Beguiling Vivien Leigh...

Vivien Leigh left her child to marry Laurence Olivier and won an Oscar for her Scarlett O’Hara. But in the end, the British actress’s life was cut short by ill health and mental illness. On what would have been here 101st birthday, we look back at the life of the beguiling actress...

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Vivien Leigh left her child to marry Laurence Olivier and won an Oscar for her Scarlett O’Hara. But in the end, the British actress’s life was cut short by ill health and mental illness. On what would have been here 101st birthday, we look back at the life of the beguiling actress...

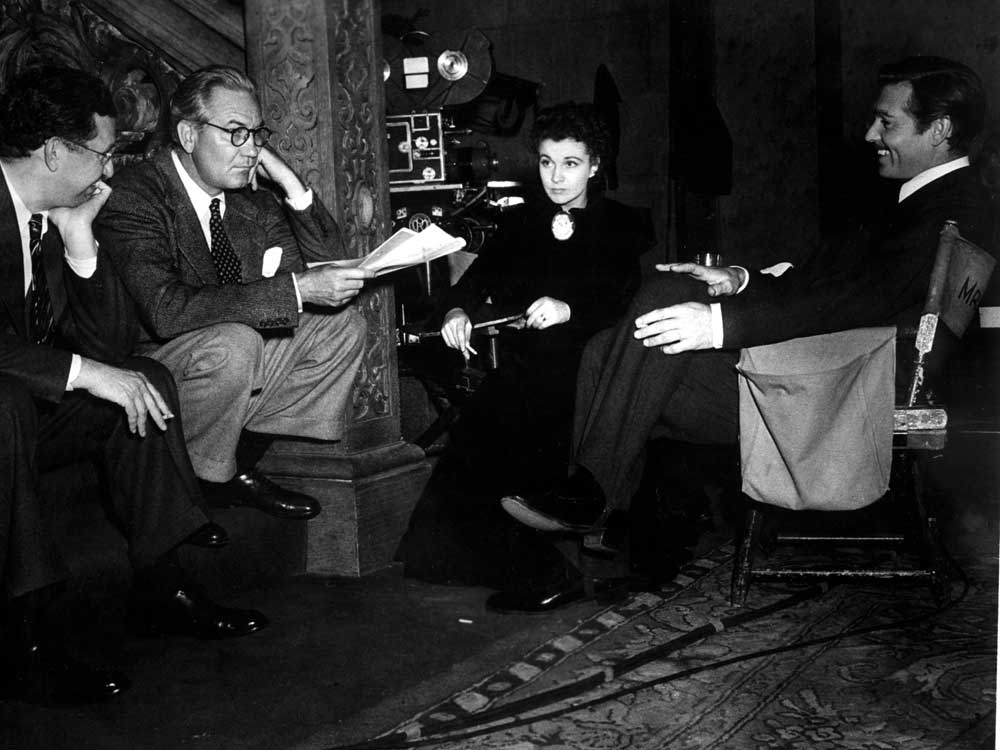

A tiny, black-clad woman walks across a Hollywood stage set, silhouetted against the flames that roar through the scenery. The fire is deliberate – filming has just begun on Gone with the Wind and this is the moment when the city of Atlanta burns. But after auditioning 1,400 actresses in a two-and-a-half-year-search that has cost more than $50,000 (about £31,300), the film still doesn’t have a female star, and its producer, David O Selznick, is desperate. He calls ‘cut’ and turns as he hears his name called. The woman steps forward, removes her hat and smiles at him as the wind whips her hair and firelight dances in her blue eyes. It is English actress Vivien Leigh. Accompanying her is Selznick’s brother, Myron, an actor’s agent. ‘Hey, genius,’ he says. ‘Meet your Scarlett O’Hara.’

The romantic saga of Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler, played by Clark Gable, has become movie legend. Gone with the Wind was awarded ten Academy Awards – including one for Leigh, the first British woman to win an Oscar for Best Actress – and became the most-watched film ever in UK film history, with 35 million cinema attendances since it was made in 1939.

It was a part Leigh was born to play. Just like Scarlett, she was a compelling mix of beauty, passion, charm and steely ambition. She would embark on an obsessive love affair but ultimately lose the man she adored. She battled tragedy and terrible illness.

Leigh’s father, Ernest, and mother, Gertrude, were both from Bridlington in Yorkshire, but they spent the early years of their marriage in India, where Ernest worked for a brokerage company. Their daughter – her real name was Vivian Hartley – was born in Darjeeling on 5 November 1913. Shortly before her seventh birthday she was sent to a Catholic boarding school in Roehampton, just outside London.

From the age of 13, when her parents left India, the family travelled around Europe, returning to London in 1931, when Leigh was 17. She was vivacious, intelligent and kind, but those early years of separation and strict Catholic schooling taught her a restraint and discipline that would help in the traumas of her life to come, while her continental travels gave her a sophistication that charmed and seduced everyone she met.

Barrister Herbert Leigh Holman fell under the starlet’s spell as they danced at a ball. They met when he was 31 and she was 18, and married a year later but, although they continued to love and care for each other for all of Leigh’s life, their romantic relationship was doomed. Leigh had already decided she wanted to be a great actress and was attending classes at RADA, although Holman assumed this was just a whim until she settled down as a wife and mother. He tolerated the small modelling jobs and bit-part film roles she secured through friends and connections, even after the birth of their daughter Suzanne in October 1933, but he wasn’t prepared for her overnight stardom two years later, when she received rave reviews in the play The Mask of Virtue under her new stage name, Vivien Leigh.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Within a year, she had a £50,000 contract with film director Alexander Korda and was preparing to leave her husband and child. ‘I loved my baby as every mother does but, with the clear-cut sincerity of youth, I realised I could not abandon all thought of a career. Some force within myself would not be denied expression,’ she said.

Ultimately, it wasn’t her career that drove her from home; it was desire. Leigh had seen the darkly handsome Laurence Olivier on stage and engineered an introduction. Although they were both married to other people, she told a friend: ‘Someday I am going to marry Laurence Olivier.’

Before Brad and Angelina, or even Burton and Taylor, there was Olivier and Leigh. They were acting’s golden couple, huge international stars whose allure was intensified when they performed together. They often played iconic lovers – Anthony and Cleopatra, Nelson and Lady Hamilton, Romeo and Juliet – and their private life was just as passionate.

When their affair began, in 1936, Leigh said: ‘I don’t think I have ever lived quite as intensely since. I don’t remember sleeping, ever; only every precious moment that we spent together.’ Olivier made the difficult decision to leave his wife, Jill Esmond, and baby son, Tarquin, and he and Leigh set up home together. They were married in September 1940 while preparing to make a film in America, with Katharine Hepburn driving them to the three-minute ceremony in Santa Barbara, California.

The Oliviers’ life was a whirl of theatre tours and movie sets, couture (Leigh wore Dior and was photographed by Cecil Beaton for Vogue) and cocktails. Vivien threw lavish parties. She would insist on guests playing croquet after dinner or swimming into the early hours and then cooking them breakfast.

Her guestlist was Who’s Who of famous figures – Orson Welles, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, NoÎl Coward, Bette Davis and Judy Garland.

But all was not as it appeared. Leigh doubted her own talent and put herself under immense psychological strain trying to match Olivier’s reputation on the stage. She had two miscarriages, and the couple was unable to have a child. Little Suzanne, meanwhile, was cared for by her father and maternal grandmother. She then attended boarding school, seeing her mother only occasionally during her childhood, but she never appeared to resent Leigh.

In 1945, Leigh suffered a severe case of tuberculosis and, although she took a year off, it left her vulnerable to a recurrence of the lung disease. But most devastating of all was the suffering caused by bipolar disorder, which saw her mood switch between terrible, crippling depression and dangerously manic phases.

In 1951, when she played the Oscar-winning role of Blanche DuBois in the film A Streetcar Named Desire, art mirrored life as she portrayed madness, vulnerability and mania. It was almost as if she and Blanche were the same person.

‘Today, actors like Catherine Zeta Jones and Carrie Fisher can talk openly about their bipolar disorder without fear it will ruin their careers, but Leigh was terrified of revealing the truth,’ says biographer Kendra Bean, author of Vivien Leigh: an Intimate Portrait.

Whispers about Leigh’s condition began as early as 1937, when she played Ophelia on stage opposite Olivier in Hamlet. Actor Alec Guinness said: ‘It was very sad. She appeared, at a very young age, to turn into a lovely stalk of chalk, and chipping away had begun, and you were there to see the flaking off.’ The cycle of highs and lows began to increase until her secret couldn’t be kept any longer.

In 1953, when Leigh was 40, she began filming Elephant Walk in Sri Lanka. Her chronic insomnia worsened and she began to hallucinate. On the flight back to LA, she tried to jump out of the plane. Back in Hollywood, she began screaming lines from Streetcar and refused to come out of her dressing room. Eventually, she was sedated, then flown back to Britain and taken to a psychiatric hospital.

At the time, there were few drugs for mental disorders and Leigh’s treatment included being wrapped in wet sheets to calm her, and electric shock therapy that she came to rely on – she even appeared on stage with the marks of the electrical pads on her forehead. ‘The Fifties were an experimental time for mental-health treatment and she could have been helped so much more by the therapy and medication available today; it was only her professionalism and will that kept her working,’ says Bean. ‘On the flip side, her personality drove her to achieve so much. Without her personal demons, she may not have inhabited roles such as Scarlett O’Hara or Blanche DuBois with such intensity.’

It was too much for Olivier to bear. After 20 years of marriage, he and Leigh divorced in 1960 and he left her for the young actress Joan Plowright. Leigh, too, had begun a new relationship, with the actor John Merivale, who adored her despite knowing the true extent of her mental illness.

Talking about the three great loves of her life to Olivier’s son Tarquin, Leigh said: ‘Herbert taught me how to live, your father how to love, and John how to be alone.’

At 45, Leigh still suffered terrible bipolar episodes but she had also proved herself as an actress and found a new closeness with her daughter, Suzanne, after the birth of her grandchildren. She continued to work, making 19 films and appearing in almost 40 plays. But in 1967, when she was 53, her tuberculosis returned.

On Friday 8 July, she died at home in her London flat as fluid filled her lungs and she could no longer breathe. Merivale tried to revive her, watched by a picture of Olivier on her bedside table.

But her legacy goes on. With this month’s national release of a digitally-restored Gone with the Wind, a new generation will discover the beauty and bravery of Vivien Leigh, one of Britain’s most legendary actresses.

The leading destination for fashion, beauty, shopping and finger-on-the-pulse views on the latest issues. Marie Claire's travel content helps you delight in discovering new destinations around the globe, offering a unique – and sometimes unchartered – travel experience. From new hotel openings to the destinations tipped to take over our travel calendars, this iconic name has it covered.