I'm All For Second Hand September and Pre-Loved - But Is Fast Fashion Hijacking the Moment and Movement?

The Green Gap, our sustainability column from Lucy Siegle, is back - this month, reflecting on the magic of genuine pre-loved clothing.

Autumn is the "season of mists and mellow fruitfulness," as Keats put it. After a seemingly never-ending summer, many can't wait for cosy evenings in, misty mornings, and sweater weather. But what really gets my heart racing is discovering a Harris tweed jacket from the charity-shop rail or a cashmere knit that still shimmers in old age so much that you don’t notice its mothball scent.

The drumbeat of pre-loved is building. Charity stats show that nearly 70% of people in the UK now own multiple pre-loved items, and over 40% say they buy and wear more second-hand clothes than two years ago.

Oxfam’s Second Hand September movement, a challenge designed to encourage people to only buy second-hand for 30 days, is a major driver. And it’s not just a fashion challenge - purists aim for second-hand everything for the month.

As Secondhand September gets underway, we ask: is pre-loved becoming problematic?

This year’s campaign is fronted by Jameela Jamil, who often chooses to rewear and recirculate. The slogan - "Dress for the World" - speaks to the power of the second-hand shopper’s agency.

But this contrasts sharply with the mainstream fast and ultra-fast fashion world, where consumers are swept into an orgy of buy-and-chuck trend-driven plastic garments with tiny lifespans.

Further statistics show that forty per cent of clothes produced are never worn, 99% of wardrobe items are worn just five times, with the Fashion Transparency Index highlighting that there is enough clothing currently circulating to clothe six future generations.

A post shared by Cosmopolitan UK (@cosmopolitanuk)

A photo posted by on

Buy-and-chuck trend-driven mania overwhelming all systems

Second Hand September deserves credit for making pre-loved garments mainstream - but in truth, it can’t afford to fail. Fast and ultra-fast fashion are overwhelming all systems, including charity donations and resale. Oxfam receives some 47 million items of "waste" clothing annually.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Around half can’t be sold through charity shops and are reprocessed at its Wastesaver facility in Yorkshire - textiles are shredded for industrial rags or exported. The Salvation Army in Kettering reports receiving around 87,000 tonnes of waste clothes annually, nearly double the volume from five years ago.

That said, demand for preloved over new clothes only continues to grow. The ThredUp Fashion Resale Report shows that globally, "resale" as a clothing category is projected to overtake fast fashion by 2028. Sales are projected to hit $350 billion globally, surpassing fast fashion’s projected $260 billion. Re-circulating garments should also give our beleaguered ecosystems a break from the environmental impacts of fashion. Which is great news, right?

Fast fashion has developed a big enthusiasm for secondhand

Well, kind of. Sadly, there's a fly in this pot of ointment. As profits migrate towards resale, perhaps it’s no surprise that fast fashion has developed a big enthusiasm for secondhand. Don’t be surprised to see more and more brands getting in on the act.

Two years ago, coinciding with Secondhand September, Swedish giant H&M launched "Pre-Loved" at its flagship Regent Street store. Zara has introduced a "pre-owned" platform allowing customers to buy, sell, repair, or donate items. But perhaps the most eye-popping is Shein’s resale platform, Shein Exchange, launched in the U.S. in October 2022—coinciding with its attempt to IPO on the New York Stock Exchange and efforts to appear more sustainable. The platform integrates into the Shein app, letting users list some past purchases with a “sell” button. While it was meant to launch in the UK, that doesn’t appear to have materialised yet.

Other brands like Dr Martens, Sandro, and The North Face partner with tech companies like Archive that take care of all the "behind-the-scenes," from listings to logistics. Analysts credit this model with scaling resale into higher volumes, quicker turnarounds, and a more systemised, mainstream feel.

To me, the irony is real - a second-hand system mimicking fast fashion, partly to manage the overwhelm that that fashion system has created in the first place. Applying fast fashion’s systems to resale risks perpetuates the core problem: overproduction, driving overconsumption and waste.

Scaling second-hand at speed also risks bringing environmental degradation, poor working conditions, and exploitative labour into resale supply chains. Trade unions and garment worker advocates warn that rising resale profits are already coming at workers’ expense, echoing fast fashion’s long-standing injustices.

A post shared by Bay Garnett (@baygarnett)

A photo posted by on

Made to last > cheap and fast

Fast fashion is making a bet that if they compete on choice, speed, and price, consumers will buy into their pre-loved with the same vigour as they buy their new stuff. But a 2022 study in the Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management found that perceived quality and authenticity are crucial for second-hand buyers. A ThredUP survey showed over 60% of shoppers prioritise quality. Anyone who’s rummaged at a jumble sale knows few fast fashion pieces can compete with the soft, luxurious cotton knits or heavy jersey weights of the recent past, made to last.

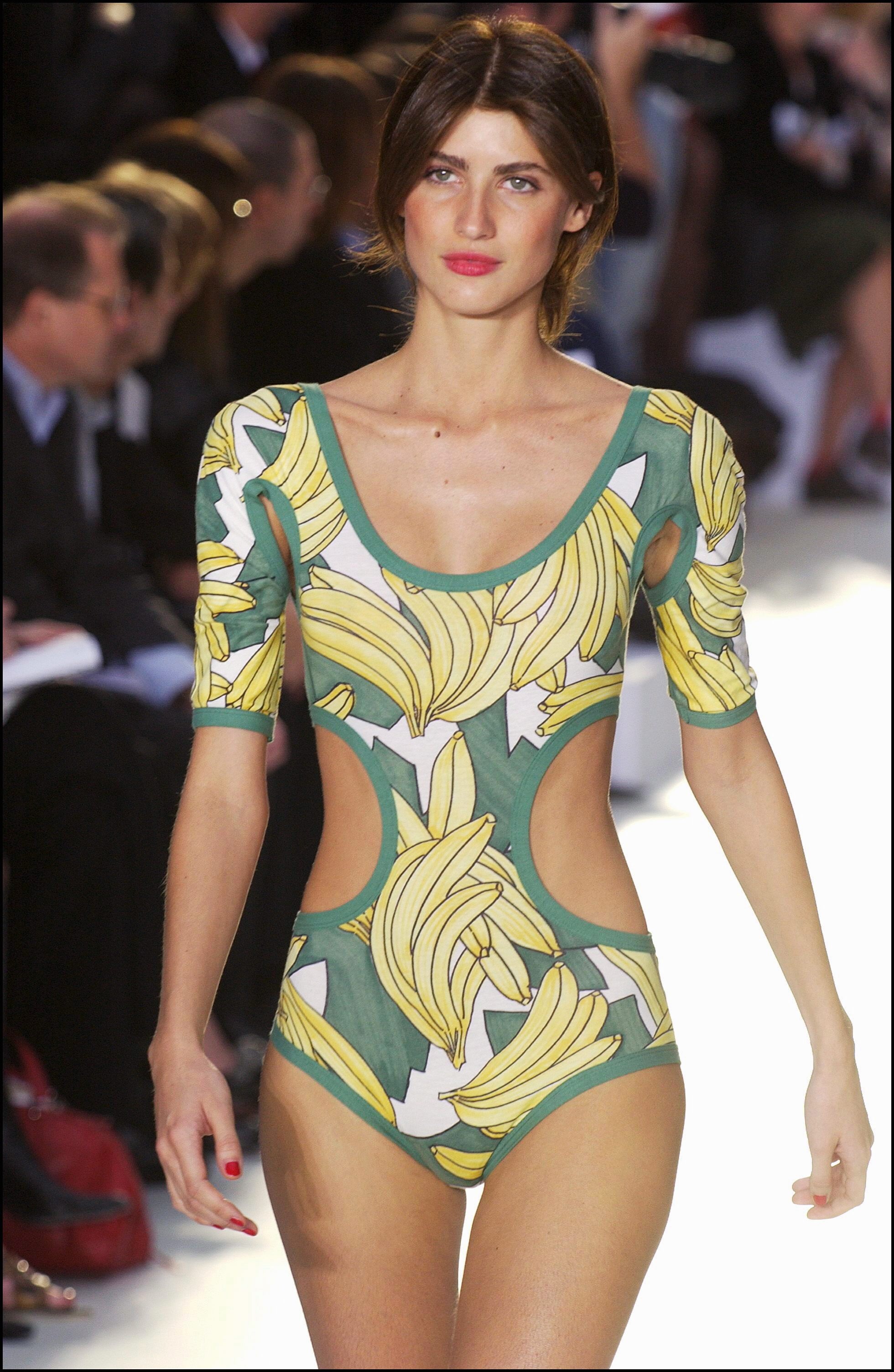

It's about the emotional "feels" too. Everyone has their vintage heroines—mine is Bay Garnett, aka "The Queen of Thrift," who championed pre-loved fashion in the 2000s. She once dressed Kate Moss in a £1 vintage banana vest from a charity shop, sparking a major fashion moment. “Charity shops made me feel like I was good at something,” Bay has said. “It wasn’t just the clothes; it was the ideas and stories behind them, and the independence of creating your own stories with those finds.” For me, this sums up the appeal of pre-loved, and it’s not something fast fashion can seek to own and dominate.

Lucy Siegle has been described as the UK’s green queen. For nearly two decades, she has championed ecological issues and sustainability on prime-time TV and for major media brands, making them relatable and relevant to all audiences.

She's the author of five books, including Turning the Tide on Plastic. But it was her 2011 exposé of the human and ecological cost of the fashion industry, To Die For, that popularised terms including "fast fashion" and spearheaded the sustainable fashion movement. In 2015, it inspired The True Cost, a hit Netflix documentary.

Lucy co-founded the Green Carpet Challenge with Livia Firth and works on climate advocacy with musician and UN Environment Ambassador Ellie Goulding. Lucy is a trustee for Surfers Against Sewage and an ambassador for WWF UK and The Circle.