We’ve found the best books of 2024 to curl up with

Must-reads and page-turners chosen by a book-obsessed writer

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What better way to spend your down time between the whirl of the party season than curled up on your favourite chair with a new favourite book?

Our final selection of releases for 2024 delivers mightily on this, with everything from creepy tales from the master of British folk horror and dystopian cli-fi (aka climate change fiction) to a brilliantly unnerving story of erotic obsession about a troll (yes, really).

Throw in a novella about—fittingly—the life-changing impact of a night spent at a party and a couple of sharp short story collections and you’ll be sorted until we return with a brace of sparkling new fiction for 2025. Slàinte!

The best new books of 2024

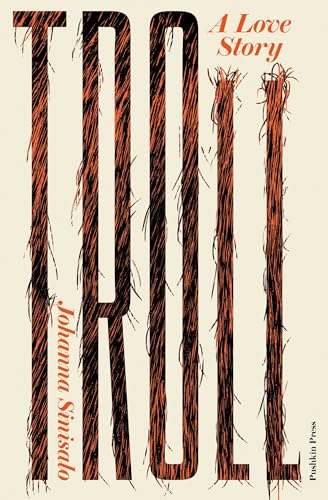

Young advertising photographer Angel is stumbling home drunk after a night out when he stops a group of teens terrorising a juvenile troll. Immediately beguiled by this strange forest creature, he takes it home with him and attempts to nurse it back to health. As Angel tries to learn more about how he can help his new roomie – who he calls Pessi – readers are treated to a fascinating history of trolls, drawn from both real excerpts from folk tales and popular songs and fictional encyclopaedia entries and news reports (the story is set in a parallel Finland where trolls – while rarely seen – are officially verified as a species). But the longer Pessi is with him, the more Angel is drawn under his spell – and the greater the danger to all those who encounter them both.

Originally published in Finland in 2001, Sinisalo’s debut novel won the prestigious Finlandia Award. With its focus on queer desire and ‘beasts’ of all kinds, this updated translation – which also nods to climate change and society’s othering of what it doesn’t know or understand – reads as if it could have been written yesterday. Clever, funny, dark and tender – it’s the love story you never knew you needed.

A legend of Tokyo’s underground scene in the 1970s and 1980s, Suzuki was a model, indie film star and prolific writer of science-fiction stories and essays about Japanese counterculture, and has been steadily building up a cult following since her suicide in 1986. This, her first novel to be published in English (it was published in Japan in 1983), tells the story of a young twentysomething Izumi hanging out at gigs and nightclubs and making terrible – and we mean terrible – decisions about men. Booze, drugs, depression and ennui are all rife. It’s chaotic and nihilistic, with much speculative mirroring of its author’s life. Fascinating.

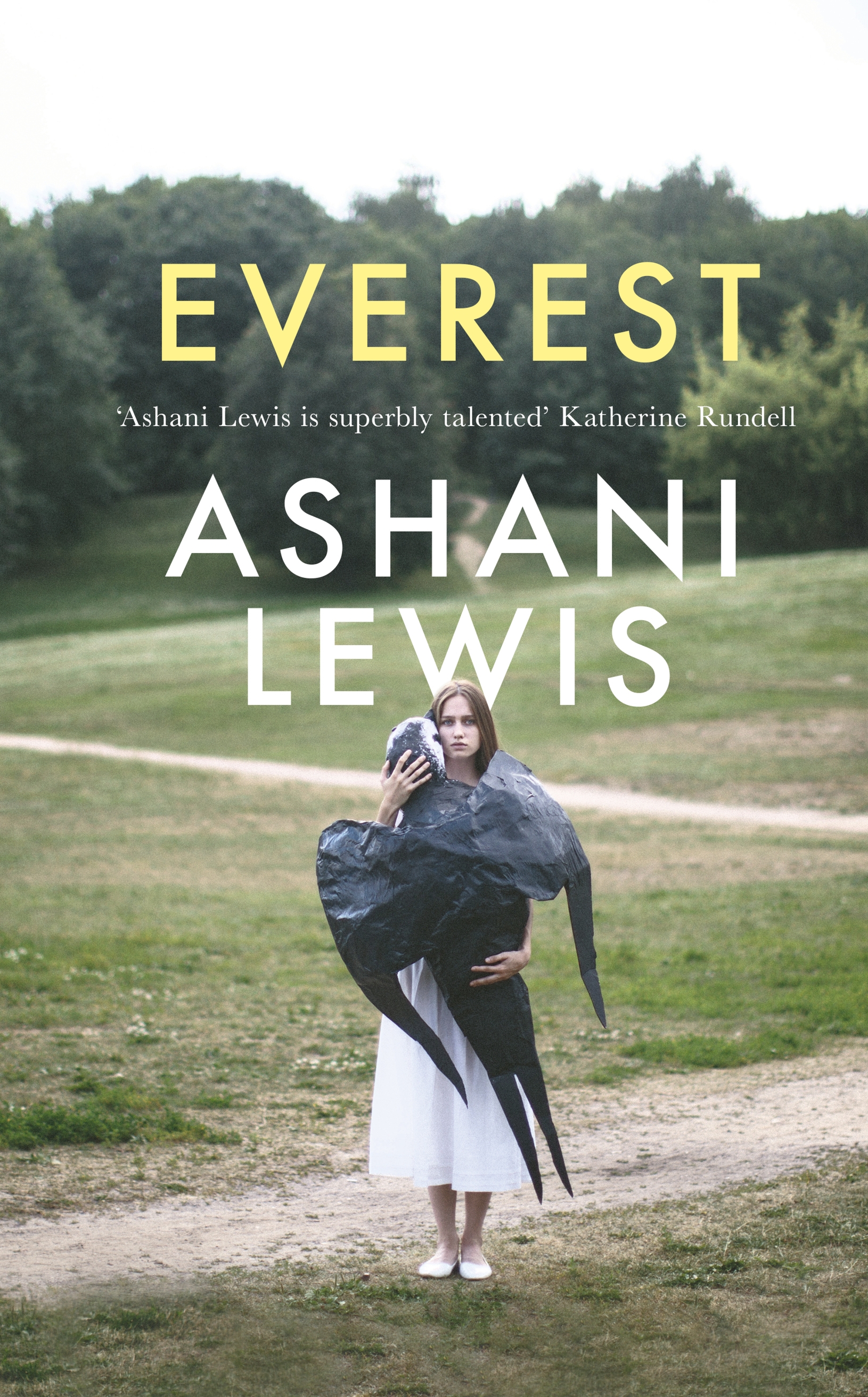

Lewis’s debut, Winter Animals, revealed her as a writer with a sharp, observational eye and this follow-up collection of short stories confirms it. She possesses a rare ability to write with both solemnity and ironic humour across the pages of a single story (and some of these are very short, almost to the point of flash fiction) – sometimes in the same sentence. ‘Linda’ – about a young woman who sees her childhood therapist in the faces and haircuts of middle-aged women everywhere – is a case in point: it closes with a killer line straight out of the psychotherapy workbook. Funny and astute, Lewis has a keen eye for both the echoing loneliness and transcendent moments of connection in our increasingly atomised lives.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning author returns with a dense, multi-layered novel about a small farming community in North Dakota’s Red River Valley. Set in the wake of the 2008 financial crash, a tragedy hinted at from the top leads the love triangle at the heart of the story as 18-year-old Gary presses his unlikely high school sweetheart Kismet into marrying him, unaware that she’s sleeping with former classmate, Hugo. Gary’s mother is thrilled at the union, while Kismet’s is distraught, another of the dynamics that power this tale of inheritance and legacy.

There are other, wider, themes and stories being addressed here, too. But Erdrich’s messaging about greed, capitalism and the damage done to both land and community from one-size-fits-all agribusiness and large-scale mining hide in plain sight alongside the day-to-day concerns and travails of her characters. (A passage about a section of land that has been rewilded, as seen through Kismet’s eyes, is a particularly powerful and memorable paeon to respecting nature.)

In true Erdrich style, there’s a nod to the supernatural in here, too, treated similarly lightly. Gary, we learn at the start, has always been unusually lucky, seemingly protected by a ‘guardian angel’ – but is he under the watchful eye of something more nefarious?

This almost impossible to categorise novel is funny, touching and full of big ideas. But most of all, it’s a story of love of all kinds and at all stages of our lives. Hard recommend.

As the only title on this year’s Booker shortlist we didn’t cover on release, it would be remiss not to include this exceptional debut in our Best Books for 2024. Set in the Netherlands in the early 1960s where the legacy of the Nazi occupation still looms large, Isa lives a perilous, isolated life in the house acquired for her family by their uncle when they were evacuated out of Amsterdam during the war. Having dedicated herself to nursing her mother through her illness before she died and with only sporadic contact with her two brothers, she is lonely and vulnerable; paranoid and brittle – convinced the maid is stealing from her and distrustful of almost everyone. And then along comes her brother’s girlfriend, Eva – brassy of hair and slippery of manner – who moves into the house while Louis is away for work, disrupt what little calm Isabelle has carved for herself. Van der Wouden’s terse, tight prose paints a beautiful portrait of fear, desire and need as the two become closer and the house slowly but surely gives up its brutal secrets. Wonderful.

Hadley is equally well known for both her short stories and full-length novels. Now, she brings her considerable talents to a new form – the novella. The tale of two sisters, Evelyn and Moira, who attend at a bohemian party in a derelict dockside pub in post-war Bristol, followed by another, very different, but equally revealing second party at a grand, if rundown, house, hosted by two men they met at the first. Sexual awakenings and follies follow as Hadley’s keen eye follows the sisters through a coming of age that leaves them both on the brink of something they may or may not be as life-changing as it first appears. And it’s all the more fascinating for that ambiguity.

Since the publication of his debut, The Loney, in 22014, Hurley has proved himself to be one of the masters of a very British kind of folk horror and this novel of interlinked stories about the supernatural and spooky goings on of a small, forgotten, fictional village in the north of England shows why. It traces the eponymous location from its founding by Celtic farmers throughout its history, with stories dedicated to different times periods over the centuries, right up to the present day and into the near future. As ever with Hurley, it’s the sense of place that’s both so chilling and alluring. A great mid-winter read.

Winton’s cli-fi blockbuster comes billed as Mad Max meets The Road and it doesn’t disappoint on either front. We’re in a near-future Australia where the once-slow creep of climate change has long since turned into all-out catastrophe with people forced to live in armed settlements and underground to defend provisions and escape the searing heat and drought. Our unnamed narrator is travelling with a young girl who it’s clear is not related to him in any way but for reasons as yet unknown has decided to help when they seek refuge in an abandoned mine that, it turns out, is not so abandoned after all. Locked up overnight as their guardian decides whether to treat them as friend or foe, the man begins to narrate his life, One Thousand and One Nights-style in an attempt to prove their credibility. What follows is a rollicking, shocking tale of what Winton clearly believes might just be our future should we continue on our present course with regard to how we treat our planet. At 500-plus pages, it’s a meaty – almost to the point of intimidating – read but once it has you in its clutches, you won’t want to put it down.

The Boy Part’s and Penance author’s first short story collection is a riotous mix of body horror, fairy tale and dystopia – with a little sci-fi thrown in for good measure. The women are complicated and the men are problematic; parasites and tapeworms abound. Subtle it is not, then, but it’s clearly not meant to be. Fun and at times surprisingly thoughtful, this is Clark at play with ideas and genres that, while they don’t always come off, are always entertaining.

A new novel by Japan’s biggest-selling novelist is a big deal. Murakami’s much-anticipated latest hits all his usual marks: the lovelorn mid-lifer unable to move on from the mysterious loss of his first love; the magical realism of the city that may or may not be a manifestation of said character’s subconscious or truly occupy another dimension, and so on. If you’re a fan, these will be familiar not only as Murakami tropes, but because the writer has already told versions of this story in two source works (a short story and much earlier novel), returning to them because, he says, he felt there was more to explore in what they had to say.

The best books in September / October

Autumn in book world is traditionally the season for much-anticipated releases by big-name authors, and September/October 2024 doesn’t disappoint.

Elizabeth Strout, Rachel Kushner, Rumaan Alam, Richard Powers and – of course (drumroll, please…) – Sally Rooney are just some of the established heavy-hitters in this edition of our round-up. But there’s plenty of fresh talent coming to bookshelves near you, too, starting with Morgan Talty’s poignant debut about belonging and legacy.

So pull up a chair and get cosy with this lot in your reading pile for the next two months, you’re not going anywhere.

Exactly as the title suggests, Rooney’s piercing fourth novel tells a story of in-between. Two estranged brothers – 22-year-old Ivan and Peter, 32 – push and pull against one another in the wake of their father’s death. Ivan is a chess prodigy who’s been struggling with his form since his father became ill, while Peter – on the surface a successful barrister with all the trappings of successful urban life – is simply struggling, and has been, we quickly come to realise, for years.

Of course, this wouldn’t be a Rooney novel if there weren’t entanglements of the sexual kind, too. On one side of the board, we have the triangle between Peter and his young (Ivan’s age) student girlfriend, Naomi, and first love Sylvia. On the other, the burgeoning love affair between Ivan and rural arts centre programmer Margaret who, at 36 is considerably closer to Peter’s age. When the dots between the brothers’ respective hypocrisies – over affairs of the heart and more – connect, sparks (and fists) duly fly.

As Peter becomes closer to unravelling, Rooney flirts with a Joycean stream-of-consciousness to narrate the jumble inside his head. This is a writer pushing herself to test and explore both her characters and her art. It doesn’t always sit neatly with her trademark cool detachment, but her willingness to do so is further proof that this so-called ‘voice of a generation’ is in it for the long haul. As are we.

Strout has been circling this for a while now. Her last novel, Lucy By the Sea, brought Lucy Barton and Bob Burgess – beloved characters of previous Strout novels – together when Lucy and her partner William escaped New York for Maine during lockdown, with a passing mention of the mighty Olive Kitteridge thrown in for good measure. Now, with Lucy and William’s move to Maine made permanent, we get them all together.

Perhaps surprisingly, it’s Bob who really gets to take centre stage as he comes out of retirement to defend a reclusive young man who has been accused of murdering his mother, while at the same time falling into an intense friendship with Lucy that threatens his decades-long marriage. Elsewhere, Lucy has been summoned to the retirement home where Olive now lives to listen to a story. The pair fall into a semi-regular pattern, sharing extraordinary tales of ordinary lives. ‘People…People and the lives they lead. That’s the point,’ notes Lucy. ‘Exactly,’ Olive replies. Few writers illustrate that point more astutely than Elizabeth Strout.

Charles has spent most of his adult life watching his daughter, Elizabeth, grow up on the other side of the river that serves as a dividing line between the Penobscot Nation and the ‘rest of the state of Maine’. She, meanwhile, has no idea who he is. As a non-Native, Charles was forced to leave the reservation when he came of age; to spare Elizabeth suffering a similar fate, she has been raised as the daughter of another (Native) man, securing her place on the official Penobscot census. But the time has come, Charles has decided, to tell her the truth, not least because ‘blood is messy and it stains in ways that are hard to clean’.

And so begins this thoughtful, complex – if disarmingly simply told – story of birthright, belonging and legacy. ‘We are made of stories, and if we don’t know them…how can we ever be fully realised?’ Charles asks at one point. The problem with stories, of course, is that while the broad facts might remain the same, the perspective and meaning changes according to who’s telling and who is receiving them. As Charles wrestles with his conscience and his past, mistakes happen and historic – potentially tragic – patterns repeat. Talty guides the reader through all of it with compassion and care. We may not be blameless, he seems to tell us, but that is not to say we are to blame. Just stunning.

Oh, somebody’s having fun! Multihyphenate funnyman Ayoade’s latest is an audacious piece of metafiction in which the writer sets out to rescue his fictional doppelganger Harauld Hughes – a once celebrated playwright and filmmaker currently lingering in the footnotes of cultural history – from obscurity. This book is a fictional record of the fictional documentary he sets out to make to do just that, recorded in excruciatingly awkward comic detail. Ayoade has created a whole Hughes universe (a Hughesiverse?), with an additional three works of Hughes’s ‘backlist’ also hitting the shelves. Here’s hoping the ‘forgotten’ films and plays themselves are in the works too.

Johnson’s slim volume of superbly creepy stories is perfect reading for spooky season – there hasn’t been a hotel this evocative of all that goes bump in the night since Stephen King immortalised The Overlook in The Shining. This hotel is a mysterious, nameless place, built on a troubled, non-specific site on the Fens where even photographic records of the building ‘have a habit of going missing’. Its superb, self-named opener delivers a potted history of all that’s to come: from the women drowned there as a witch to the student filmmakers who disappeared from the site after breaking in to record its alleged hauntings on the night The Hotel burned to the ground, leaving only their scanty recordings behind, Blair Witch-style, in Room 63. Brilliantly chilling.

Local schoolteacher Silvia goes missing the day after one of her pupils commits suicide. Rumours abound as word of both incidents spreads through the small Italian village where they live. Tanet, however, isn’t interested in turning this into a will-they-won’t-they-find-her thriller. As readers, we quickly come to know the missing teacher has followed a trail and found refuge – fairy tale-style – in a dilapidated cabin deep in the woods. And, shortly after, that someone watchful knows where she is. Instead, the author chooses to take her narrative into far more intriguing psychological territory as we disappear into the heads of various town residents for their take on the incident and the wider machinations at play throughout the villagers’ lives. With a strong, almost magical, undertow in its depiction of Silvia’s woodland surroundings and her mental state, this is a powerful exploration of the fragility of the ties that bind us to society and loved ones. That it’s based on a real-life incident in which a relative of the author disappeared in similar circumstances makes more extraordinary still.

Shy, sickly student Mieczyslaw Wojnicz arrives in the Guesthouse for Gentlemen – a health retreat, high in the mountains of what is now Poland – on the eve of WWI. Returning to his lodgings, he finds a woman dead – the wife, he is informed, of the establishment’s owner, who seems more put out by the general irrationality of women than the specific loss of his spouse. Readers of the Nobel Prize-winning writer’s work will recognise this as familiar-ish territory for Tokarczuk. There’s much more for readers old and new to enjoy in this slyly funny folk horror where magic mushrooms and parasitic worms are on menu and the ‘landscape takes its sacrifice’ annually around the time of the November full moon. A deliciously off-centre delight.

Former federal agent Sadie Smith is now a solo spy-for-hire after a case she was working on collapsed at trial due to alleged entrapment of the accused. These days, however, Sadie’s honeytrapping skills and lack of anything close to a moral compass are exactly what her clients pay her for. In this instance, the infiltration of a group of eco-warriors living on a commune in rural southern France who she gets to know long before she meets them after hacking email correspondence between the group and their leader’s mentor, Bruno. This veteran of Paris’s 1968 May Day protests is now living off-grid and, in part, completely underground nearby. His presence and philosophical discourses on Neanderthal man, the cosmos and more add a fascinating and fierce sidebar to what is otherwise modelled as a traditional spy novel, with hard-drinking sex bomb Sophie a match for anything that genre has seen before. More than deserving of its place on this year’s Booker shortlist, this is funny, intelligent, genre-bending writing at its best.

A collection of eight new short stories, each of which – as the title suggests – has been written by two writers working together. It’s a clever premise and fascinating to see how two creative brains co-mingle on the page, from the relatively straight approach of the sweet-turned-deliciously-dark approach of Ely Williams and Nell Stevens’ ghost-story opener Merrily Merrily… to considerably more esoteric and experimental treatments, such as those by Gurnaik Johal and Jon McGregor in Junction 11. It’s a credit to the calibre of the writing talent on display and their respective willingness to give into the process that what could so easily have resulted in discord does in fact, for the most part, deliver a suite of clever harmonies. A treat.

Award-winning poet Sax’s debut novel opens on a trigger-warning premise, telling the story of young queer activist Ezra in the liminal period between life and death after setting himself on fire as an act of protest at a rally outside Trump Tower in 2016. What could have led him to this shocking act is explored in fragmented, lyrically forensic prose that stretches back – through the friendships and alienation of first school, then college; through Ezra’s first romantic and sexual awakenings in the small US town of his childhood; and through stories (and folk stories) of his Jewish ancestors. The result is a rich, densely woven patchwork of a life that is at times bleak, at others funny, yearning, and – ultimately, surprisingly, given the context – hopeful.

When novelist Oscar posts a derisory comment about movie star Rebecca online, she responds with the salutation of the title, setting both the scene and the tone for what follows. Related as a series of email exchanges between the pair – interwoven with posts by Zoe, a feminist blogger who has MeToo’d Oscar for his behaviour towards her when she worked as his PR – the mutual antagonism of their early correspondence evolves into something more pressing when Covid strikes and France goes into lockdown.

For Oscar, who has previously declared getting ‘blitzed’ as the ‘Tabasco’ he always reached for to spice up the blandness of everyday life, Rebecca becomes the proverbial port in the stormy seas of his sobriety; a favour that is reciprocated when career junkie Rebecca – refusing to be forced to order her drugs in ‘office hours’ while Paris is under curfew – decides to do the same. But this is no holier-than-thou tale of paths to enlightenment. Despentes – a rock ’n’ roll novelist if ever there was one – revels in her characters’ flaws as she rages against the machine, offering insights and assessments into everything from addiction and class to sexism, ageism, digital pile-ons and more. Wry, intelligent, often laugh-out-loud funny – definitely not one to miss.

Powers’ doorstopper of a new novel is expansive in every sense, opening with the Tahitian creation myth in which supreme being Ta’aroa uses the shell of the cosmic egg that’s housed him to create the universe (styled here as being driven by a desire to escape the emptiness of his solitary existence). It’s a beautiful metaphor for all that’s to come – a looping, lyrical dive into our threatened oceans, narrated in part by Todd, a lonely boy obsessed with board games who grows up to establish a vast, networked computer game called Playground, who we meet just as he’s been diagnosed with a form of dementia. His estranged friend Rafi, meanwhile, lives on a tiny island in French Polynesia with artist Ina (a mutual friend from college) where the already fragile ecosystem is under threat from a consortium determined to build a floating city off-shore. The now elderly scuba diver who first inspired Todd’s fascination with both the ocean and computing when he was young, just happens to live nearby. So yes, there’s a lot going on. But Powers knows what he’s doing and this lyrical love letter to our planet – and our oceans, especially – is a delight.

The Girl on the Train author is back with a thoughtful tale – more mystery than the thriller it’s described as – that follows art expert Becker as he attempts to track down the missing pieces from a bequest by a reclusive artist Vanessa Chapman. After a piece of her work has been revealed to contain what appears to be a human bone, Becker travels to the remote Scottish island that served as the artist’s home and studio for the last decades of her life to meet Grace, the executor of her estate. Chapman’s estranged husband disappeared without a trace 20 years before – could the bone be his?

If the set-up sounds explosive, the novel itself for the most part is not, which is not to say it isn’t fascinating. Propulsively and richly told, it focuses instead on a clear-eyed and thorough analysis of Chapman’s artistic practice alongside her tangled life and relationships, much of it related through journal entries that offer insights – and may well hold the key – to both the missing work and the ghosts of the past.

If the subjects our novels are written about are a reflection of the times we live in, then one of the key obsessions of our time is money – who has, who wants it, what they do with it and what they’ll do to get it. Unsurprisingly for an author fascinated by class, race and society, Alam’s follow-up to dystopian bestseller, Leave the World Behind, is a fully paid up member of this flourishing sub-genre (see also Taffy Brodesser-Akner and Kiley Reid, whose 2024 releases tread similar thematic ground). We meet former teacher Brooke as she lands a promotion at a New York non-profit foundation funded by an ageing billionaire who has decreed his legacy lies in giving away his money to good causes before he dies. Greed, inevitably, overtakes Brooke’s good intentions – and Alam has a lot of fun watching her fall.

The How To Kill Your Family author’s follow-up is another eat-the-rich caper chock full of characters for its readers to love to hate. Ponzi-scheming hedge funder Anthony dies in thoroughly inauspicious circumstances at the peak of his lavish 40th birthday celebrations, leaving wife Olivia and their four adult children to clean up the mess. Anthony watches on from the afterlife, unable to move on until he remembers his own cause of death as secrets and lies are revealed – aided by a wannabee podcaster, whose naked desire for fame is dressed up as a delusional pursuit of ‘truth’ at all costs. Everyone is vile, which is rather the point, even if it does leave the reader with nowhere to place their allegiance or sympathy. But it is funny – and bound to be another enormous hit.

More September/October books in brief:

- Our Evenings, Alan Hollinghurst: The Line of Beauty author returns with a decades-long tale of two men, Dave and Giles, from their first encounter as schoolboys to their very different careers as actor and politician, respectively. Now in his sixties, the novel is narrated by Dave, as he looks back on his life and loves as a gay man coming of age in a rapidly changing world.

- Night of Baba Yaga, Akira Otani: This queer gangland Japanese thriller is styled as Kill Bill meets The Handmaiden meets Thelma and Louise – and from violence to sex to friendship, that pretty much nails it on all fronts.

- Our London Lives, Christine Dwyer Hickey: It’s 1979 and teenage runaway Milly lands herself a job in a central London pub just after arriving in the capital from Ireland. There she meets rising boxer Pip, and a faltering, decades-long friendship and on/off love affair between the pair ensues. As much a love letter to – and lament for – the changing face of London as a chronicle of Milly and Pip’s star-crossed story.

- Annihilation, Michel Houellebecq: The enfant terrible of French literature is back with the English translation of his most recent novel (published in France in early 2022) and he’s claiming it to be his last. Expect his usual provocative fare in the politics of the thriller set-up, but there’s a softer, sadder side inside this too, with love and death, depression and grief all met head-on.

The best new books of July / August

We’re back with this year’s offering of brilliant new reads that are sure to keep the pages turning for you throughout 2024. In the spirit of that newness, we’ve given ourselves a little refresh, with a more detailed, bimonthly offering of fully reviewed must-reads and recommendations, supported by a flurry of additional favoured titles in brief.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Whether you’re spending it pool- or city-side, what better to keep you company through these long, lingering days and nights of high summer than a healthy stack of new releases.

From a heartbreakingly vivid contemporary ghost story to a triumphant – and chilling – take on the myths of Ancient Greece via Jazz Age New York and, er, Eastbourne, we’ve got you covered. Just don’t forget the SPF.

Wyld’s quietly devastating fourth novel is her most accomplished yet – and that’s saying something for an author who has been garlanded with praise and awards since her 2009 debut. Separated broadly into three timelines, it opens in London where freshly minted ghost Max is surprised to find himself haunting the Tulse Hill flat he until very recently shared with his girlfriend, Hannah. As Max tries to piece together his final moments, Hannah’s own past unfolds to the reader – not only in the weeks before Max died, but further back, to her complicated childhood in rural Australia, where secrets of all sorts lay literally and metaphorically buried. Wyld manages the complexities of both her characters and her narrative with control, compassion and more than a little well-judged humour as truths are excavated and revealed. It all adds up to a deeply moving portrait of decisions made and paths not chosen and the ripple effect as their impact echoes across generations and lives.

The follow-up to Brodesser-Akner’s whip-smart debut, Fleishman is in Trouble, is a bigger novel in every sense. Where her debut was largely focused on the marriage and milieux of the couple in question, Long Island… sprawls – across generations, decades, geography and the corrupting influence of wealth on both those who have it and those who do not. It opens at breakneck speed in 1980 with the kidnap of millionaire Carl Fletcher from outside his home, and barely lets up from there. When Carl is returned, the family do their best to put the incident behind them. But that is not, as we all know, the way trauma works and Brodesser-Akner follows each member of the family, with a particular focus on Carl’s children – sex- and drug-addicted Hollywood screenwriter Beamer, anxiety-riddled lawyer Nathan, and anti-capitalist Jenny – as they wrestle with its fallout.

In the six years since Barker published the first instalment of her reinterpretation of Homer’s epic poem The Iliad, told from the perspective of the women caught up in the 10-year battle for Troy, feminist ‘retellings’ of Greek legends have become a publishing phenomenon. But as this – the final part of her trilogy – reveals, no one does it quite like she does. The fates of Cassandra and Clytemnestra take centre stage here as warrior king Agamemnon returns to the island from which he sacrificed his daughter in exchange for fair winds to sail his men into battle a decade earlier. Both women have good reason to want to see him dead and Agamemnon’s end, when it comes, is as viscerally satisfying as it is inevitable. A chilling and triumphant end to the trilogy.

A thoroughly satisfying new collection of stories by the writer of last year’s Walter Scott Prize-shortlisted The Sun Walks Down, each of which is connected – by varying degrees and across decades and continents – to a 1990s serial killer who plucked his victims from the highway of the title and buried them in a forest south of Sydney. If that all sounds rather grim, far from it. With stories ranging from a group of teenage girls on a school trip to Rome to the presenters of a pair of ‘murder-adjacent, comedy-adjacent’ true-crime podcasters via a Hollywood actor hoping for reinvention, McFarlane brings deliciously dark humour to her sharp-eyed insight into the human psyche, and delivers it in crystal clear prose. A delight.

Grabowski’s quietly commanding debut is a novel of interlinked stories divided between the ‘Before’ and ‘After’ of the sudden death of a teenage girl in a small coastal US town. Each chapter is narrated by a different woman who is more or less directly related to the tragedy – the disillusioned student guidance teacher who discovers a secret relationship between a colleague and a student; the grieving mother whose guilt continues to tear at her; the teenager who fled the scene, and so on. Together, they build up a picture of a town riven not only by grief, but the legacy of economic failure in contemporary USA. Complex and considered, it refuses to deal in easy answers.

In this profoundly moving study of family, motherhood and relationships, Edie – who has been living in a kind of arrested development as the third party in wealthy socialites Joanna and Harry’s polyamorous marriage since shortly after being thrown out of home aged just 16 – is forced to face her past when her long-estranged mother dies. Now in her fifties, Edie is forced back into the narrow world of her childhood when she returns to London for the funeral and to help half-sister Simone clear out her mother’s flat. As she sieves through the detritus of the apartment in which she was raised and family secrets are revealed, Edie begins to see how the patterns of the past have bled into her present. Is she finally ready to face her own reckoning?

The You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty author’s new release is not going to be for everyone: subtle it is not. But assuming you do have the stomach for the sex, lies and video that proliferate throughout, let’s just say it is quite the ride. Set over the course of a weekend in the fictional city of New Lagos, it opens on a heartbroken Aima preparing to leave Nigeria once and for all having broken up with her boyfriend Kalu for refusing to put a ring on it. She gets as far as the airport before changing her mind. The odyssey of drugs and sexual experimentation that follows is matched by the antics of her ex, who throws himself into a sex party in an attempt to forget his heartache and ends up with a price on his head. Add two prostitutes back in the city for the weekend, a corrupt pastor and a whole lotta drama and it all adds up to a tale that is so wilfully decadent it quickly veers into the highest of high camp.

Franklin’s astonishingly assured debut follows disaffected millennial Mary, who’s just been let go without fanfare from her marketing job at a London tech start-up. She decides to blow the last of her cash on a trip to Ibiza, where she meets recovering addict and chemist Tom, who’s working on what promises to be a ground-breaking new antidepressant. When Mary accepts a job at what promises to be a similarly revolutionary new dating app – spearheaded by her charismatic and manipulative ex, Lara – it doesn’t take long for their respective worlds of tech and pharma to collide. The fallout, when it happens, is epic.

Watson’s debut Little Scratch – a freewheeling stream of consciousness across a day in the life of a woman struggling to deal with a recent sexual assault – was a literary sensation when it was published in 2020. This follow-up is on similar ground, insofar as it is another intensely close study of its narrator’s response to a life-defining incident – in this case, the death of her estranged brother in a car crash. Plotted over the course of a weekend, it dives deep into their personal history and that of their family, inviting questions about decisions made and perception and whether the experiences we’ve always seen as defining are that way by objective reality or choice.

The unforgiving beauty of 19th-century Lapland serves as the backdrop to Pylväinen’s transcendently epic love story. Lutheran minister Mad Lasse is finally beginning to have some success in his attempts to convert the local Sámi people to his faith when young reindeer herder Ivvár meets – and falls for – the minister’s daughter, Willa, who sets out with the herders on their annual migration. What follows is a soaring yet powerfully intimate tale of a people, culture, history and landscape that for all its careful research – Pylväinen spent six months living with Sámi herders in Finland – remains very much a tale of the heart all the way to its shattering end. Stunning.

This sprawling, multi-generational saga captures the brittleness of generational wealth and the divide between the haves and have-nots of a community in the unforgiving Adirondack Mountains in Upstate New York. It opens in 1975, on the morning Barbara Van Laar – wayward teenage daughter of the family who own much of the surrounding land – is reported missing from summer camp. Her disappearance echoes that of her brother, Bear, several years before and coincides with the prison escape of the serial killer widely believed to have been responsible for that incident. As the news spreads and the search begins, the dark secrets at the heart of the Van Laar family and residents of the nearby town begin to be revealed. Superbly plotted, it’s a great poolside read.

Vita has been laid up in bed for months with a mystery illness that continues to escape diagnosis. She hasn’t spoken to her sister in weeks and partner, Max – a busy surgeon – has to leave her for long stretches on her own, with only her goldfish Whitney Houston and the ghost of a centuries-dead Italian nobleman for company. When a leak from upstairs threatens to turn into a flood, Vita is forced to journey upstairs to the neighbouring flat, which sets her on the path to a tender, tentative friendship with recently bereaved neighbour Mrs Rothwell and her lodger, Jesse. As stories and intimacies pass between them, Vita gradually reconnects to long-buried traumas that have brought her here. A sensitive, astute, gently funny study of the powerful intersection between body and mind.

Baltasar’s intriguing follow-up to her International Booker-shortlisted Boulder comes in at just a little over 100 pages, in which not a sentence is wasted. We meet our unnamed narrator on the day she has determined she will become pregnant. A handful of pages later that attempt has failed, her growing disquiet has seen her leave her university research job, dabble unsuccessfully in a handful of others and determine the only way forward is to ‘flee’ from her life. So begins a quest to live off-grid in the mountains, reconnect with nature, herself and a fair number of random strangers – and all the while the search for meaning goes on.

Young mother Kit has been struggling with parenthood, work, the truth – all of which is related to her ongoing grief from her sister Julie’s recent death. A weekend away with her gay best friend is supposed to help, but when Kit returns home closer to unravelling than ever, it’s clear something has to change. This sharp, funny, howl-of-pain of a novel has much to say about sisterhood, motherhood, friendship and love.

If you’re after a little cosy crime to keep you company on your sun lounger this summer, then Cunningham’s debut – a funny, off-beat murder mystery – is the one to pack. Risk-averse life insurance actuary Una is horrified to learn that a sudden spike in deaths in the seaside town of Eastbourne (where, by chance, her widowed mother lives) has thrown her numbers out and sets out to find out why. Once there, she uncovers to a link to a local lottery syndicate, led by her mother’s new fiancé, Ken. Can she uncover the truth about the murders before the next one – which according to her calculations is scheduled for Ken and her mother’s wedding day – takes place?

Lusk’s second novel tells the real-life story of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (who, incidentally, inspired Aunt Harriet in his debut The Second Sight of Zachary Cloudesley), whose many achievements include introducing an early form of inoculation for smallpox to Britain in the early 18th century. Mary was, as the title suggests, neither shy, nor retiring by nature, making as many enemies as she did friends. Lusk captures her complexity with wit and compassion in a globe-trotting plot that’s sure to be catnip to historical fiction fans.

Stewart’s culinary whodunnit blends Boiling Point with The Bear and serves it up with a sprinkle of surrealism and more than a soupcon of black humour on the side. Waitress Marley is in the kitchen of London restaurant of the moment, Midgard, waiting for her shift to begin when she realises something’s not quite right; she appears to be trapped between the refrigerators and unable to move or call for help. The truth about her circumstances gradually unfolds over the course of what is revealed up top to be the final night of the service. Told in extended chapters focused around each of the restaurant’s seven tables, A little rich in places perhaps, but overall, it’s a fun and pacey summer read.

Affecting coming-of-age tale of thwarted first love, written as a series of journal entries by narrator Daniel to his college roommate, best friend and sometime lover, Sam, who we learn in the opening pages has just died. Where the novel really comes into its own is in the parallel story of Daniel’s deepening understanding of his family history on a summer visit to his Mexican homeland where he learns about his namesake and over the course of several weeks becomes more confident in exploring and understanding his own sexuality.

More July/August Books in Brief

The best new books of 2024

- Moderate to Poor, Occasionally Good, Eley Williams. That title – taken, weather watchers and insomniacs will be aware, from the shipping forecast – says everything about the funny, offbeat-to-the-point-of-nerdy nature of Williams’ newest short story collection. And that, in our book, is a very good thing.

- Heart, Be at Peace, Donal Ryan. A return to the landscape – and characters – of Ryan’s widely acclaimed first novel, The Spinning Heart. Each short chapter is narrated by a different member of the community, building up a similarly moving and incisive take on small-town Ireland life.

- The Instrumentalist, Harriet Constable. This vivid retelling turns the spotlight on forgotten 18th-century Venetian violinist and orphan Anna Maria dells Pietà – who studied under Vivaldi and was a true star of her day.

- Ex-Wife, Ursula Parrot. Billed as the summer’s hottest rediscovered classic, Parrott’s debut about a young divorcee trying to find her way in Jazz Age New York was a bestselling sensation on release. The men are cruel, the women are feisty but inevitably – sometimes brutally – put-upon.

- Wife, Charlotte Mendelson. Fledging academic Zoe falls for department senior, Penny, right from the off and a whirlwind relationship ensues. Years later and she’s trying to extricate herself – and their two daughters, conceived with and co-parented by the brother of Penny’s ex – from this most complicated and toxic of relationships. Grimly funny.

Best Books from May/June

Our May/June round-up of new fiction releases lands just as the weather is heating up and has all you need to start building your ultimate summer TBR pile.

In the mood for a stonkingly good (and swooningly romantic) time-travel caper? Or perhaps a sharply observed marriage story featuring an AI sex doll is more your bag? Or how about a masterful, end-of-days spin on King Lear?

Alongside these, we have two very different – yet equally heart-breaking – tales of small-town Ireland, a love letter to big city life set across one scorching hot London weekend, a century-spanning art-murder mystery and a whole lot more. Read on!

After six rounds of interviews for a job so top-secret she has no idea what the role actually is, our unnamed narrator – a British Cambodian translator-consultant at the Ministry of Defence – becomes a handler for one of a handful of individuals (‘expats’) who have been plucked from history. ‘We have time travel,’ she is informed, ‘like someone introducing the coffee machine’ – and the shrug that comes with those lines sets the tone for the rollicking tale that follows.

Her charge is the devilishly handsome and charismatic Commander Graham Gore (based on the real-life Victorian polar explorer who died in the Arctic in 1845). Bradley has a lot of fun with the fish-out-of-water time clash as Gore and the other expats get to grips with everything from modern plumbing to Spotify. But as our pair fall inevitably, swooningly in love, the battle to get hold of the device that allows all these hijinks in the first place builds to its page-turning climax. Pacey, witty, intelligent, with a deft handle on some big themes – immigration and colonialism among them – The Ministry of Time is quite simply a cracking read.

High school teacher Dolores is aware that all is not entirely well in her marriage, but it’s only when she discovers a programmable AI sex doll (the Zoey of the title) hidden in the garage that she realises just how bad things have become. Left alone in the marital home, she begins to chat with Zoey who serves as a sounding board to her insecurities and fears. What could have been played for easy laughs or simple shock-factor becomes a fascinating dig into Dolores’s past as she begins to grapple with her emotional frailties and confront long-buried traumas. A funny, insightful tale of love and complicated families.

There’s nothing showy in Tóibín's follow-up to his 2009 novel, Brooklyn, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t pack its own quietly powerful emotional punch. It picks up the story 20 years on from when Eilis sailed back to America from her trip home to Ireland (and romance with local lad, Jim Farrell) to settle down with secret husband Tony. The couple are now living on Long Island with their two teenage children. Both life and marriage, while not entirely without their frictions, are steady enough. That is, until a man arrives on the doorstep and calmly tells Eilis that his wife is pregnant with Tony’s child.

Eilis’s response to that bombshell is a steadfast refusal to accept what others see as inevitable. She sets an ultimatum and returns to Ireland for her mother’s 80th birthday. There, a delicate and complicated chain of events is set up and disrupted as the key characters from Brooklyn are brought back together and forced to reckon with the consequences of paths not taken. A masterclass in subtle, complex emotion.

Set in a near-future city teetering on the brink as rising waters threaten all-out climate collapse, Armfield’s follow-up to Our Wives Under The Sea follows three queer sisters – Irene and Iris and half-sister Agnes – as they come together in the wake of their father’s death. The set-up is a clear and knowing riff on King Lear, and like Shakespeare’s great tragedy, this is ultimately a tangled emotional tale of inheritance and legacy. But what, exactly, is being inherited and whose legacy is it? With each sister narrating their own story, we’re given a powerful insight into the traumas and events that have shaped all three of them. But it is the fourth narrator – the drowning City itself – that underscores the novel’s wider themes and the eerie sense of creeping dread that, as the waters rise, builds to its catastrophic denouement.

Mostly set over one hot (in every sense) weekend in June 2019, McKenna’s debut is an exhilarating, freewheeling love letter to London. It centres around a group of friends who have known each other since childhood and moved to the city to fulfil dreams, pursue ambitions or simply escape the narrowmindedness of small-town life, but who now, aged 30, are beginning to question their choices and consider what follows.

Broke and pregnant, failed artist Maggie is on the cusp of leaving the city with her partner, Ed, who has not been entirely honest to either Maggie or himself about his past and desires. Her best friend Phil is in love with his housemate, Keith, whose open relationship with his long-term boyfriend is proving to be difficult to navigate. Phil’s mother Rosaleen, meanwhile, grapples with her own complicated history as she attempts to share some difficult news with her son. As the city rallies round the story of a whale that has become stranded in the Thames, the friends and their friends’ friends, and their friends’ friends (and so on) come together at a house party to end all house parties. Truths are aired, secrets are revealed and confusions laid to rest. Now bring on the summer!

Three novels in and husband-and-wife writing partnership Ellery Lloyd are carving out a clever niche for themselves: ingenious, well-written plots with thought-provoking, zeitgeisty themes (‘lost’ women in art history serving as a key one here) that never come at the expense of pacing or plot. This one – an art-murder mystery set over three timelines that span roughly a century – is another winner from the pair, a darkly glamorous and twisty caper that is their most ambitious and compelling to date.

Murrin is an acclaimed writer of short stories, which may go some way to explain how this, his debut novel, is such an astonishingly assured piece of writing. Set in 1994, as Ireland’s divorce referendum is about to be put back on the political table, it centres around the lives – and loves – of the women in a small Donegal town as bohemian poet Colette returns, having left the lover she fled to Dublin to be with several years before. Desperate for her estranged husband to let her to see her children, she enlists the help of Izzy, whose decades of marital frustration with regard to her controlling local politician husband, James, make her sympathetic to Colette’s plight. But as Colette spirals, the town closes ranks. An intricate and deeply compassionate study of women’s lives and the forces that shape them.

In this, July’s second novel, her unnamed protagonist – a semi-famous, middle-aged, multidisciplinary artist who may or may not resemble the writer herself – leaves her husband and child in their LA home and sets out on a cross-country road-trip to New York. She gets as far as a neighbouring suburb, where she checks into a motel, remodels the room, falls hard for a young, married, wannabe dancer and ends up staying for the full three weeks of her vacation. The stay is a catalyst for the entire upending of life as she and her husband know it as she explores her sexuality, analyses perimenopausal lust (of which – warning – there is a lot), and generally changes her life in any and every way she can. Vivid, frank, and for all its endless naval-gazing, very, very funny – this is menopause, baby, but not as you know it.

As you might be expected from the author of meaty non-fiction works Art Monsters and Flâneuse, there’s a lot going on under the hood in Elkin’s debut novel. Set in the same Paris apartment over in two timelines it tells the story of two couples. French American Anna – a psychotherapist who has suffered a breakdown following a miscarriage and is unable to work – and her largely absent lawyer husband, David, open the novel in 2019 as Anna strikes up a friendship with younger neighbour and guerrilla feminist Clementine. Later, we meet nascent feminist and psychotherapy student Florence, who lived in the apartment her husband, Henry, in 1972. Both women are converts to the ideas of controversial French psychoanalyst Lacan. Both women are wrestling with ideas around fidelity, desire and motherhood. As the novel progresses, its themes and to some degree characters intertwine. A challenging and satisfying read about the lives we project onto others as much as those we build for ourselves.

Darraj’s debut – told in a series of interlinked stories – explores the lives and ties of a diverse community of Palestinian Americans with humour and compassion. A teenage girl’s discomfort over the racial implications of her high school production of Aladdin is handled with wit and nuance, while the slow-drip horror of a husband and father’s possible implication in an incident that sets the internet alight is unveiled with a restraint that makes its revelation all the more chilling. Elsewhere, intergenerational differences and the clash of the old world (Palestine) and new (America) are explored from both sides with keen-eyed humanity and understanding. But it’s the closing story, in which police officer Marcus honours his dead father’s wish to have his body returned to Palestine for burial, that ties the novel’s many themes and threads together in an extraordinarily moving tale made all the more powerful by our knowledge of all that’s come before.

Mellors’ bestselling debut Cleopatra and Frankenstein explored the messy, complicated romance of the bohemian couple at its centre. For her follow-up, the author turns her attention to the messy complicated lives of three sisters – Avery, Bonnie and Lucky Blue – who are drawn together in the wake of their fourth sister’s accidental death by overdose. In both, addiction and self-destructive behaviours are rife. Blue Sisters, however, uses familial patterns and rivalries to dig deeper into Mellors’ exploration of dependency of all kinds.

There are undeniable shades of Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Women, Other in this debut, which follows the lives of the extended family and friends of four sisters across several decades in and around Washington DC across 13 interlinked stories. Sanders has fun playing with her characters as alignments and allegiances shift and change with the perspectives, points of view and timeframes of each story’s narrator.

Thirtysomething translator Nat moves to an oppressively small rural town where she rents a rundown property and adopts a skittish, badly trained dog. Struggling to fit in and afraid to deal with the threat of her bullying landlord, she accepts the terms of an unusual offer that shifts her standing within the community and her own understanding of herself. Nat’s inability to ‘translate’ her own actions and behaviours drives this intriguingly ambiguous tale of autonomy and power.

More May/June Books in Brief

- Openings, Lucy Caldwell. The third collection of stories from the 2021 National Short Story Award winner offers 13 tales of relationships, family and motherhood, all written with Caldwell’s characteristic clear, concise prose and keen eye for the space between who we are and who we present ourselves to be. A delight.

- Bright I Burn, Molly Aitken. Aitken’s lyrical second novel tells the story of Alice Kyteler, the first recorded person in Ireland to be condemned as a witch. It may be set in the 13th century, but its fierce rebuke of the patriarchal constraints that lead Alice to her fate resonates powerfully to this day.

- Hold Back the Night, Jessica Moor. Former nurse Annie reflects on the path that led her from her training as a naive student in a private psychiatric hospital to a widow taking in a series of HIV-positive lodgers at the height of the AIDS crisis in 1980s London.

- A Cage Went in Search of a Bird, various authors. 2024 is the centenary of Kafka’s birth and this collection of determinedly ‘Kafkaesque’ stories from a storied list of writers (Ali Smith, Yiyun Li, Naomi Alderman and Helen Oyeyemi among them) has been specially commissioned to celebrate. A mixed, but intriguing, bag.

- (Paperback release of the month) August Blue, Deborah Levy. A celebrated concert pianist blows up her career by walking off stage mid-performance in this tale of other lives and paths not taken. In a market stall in Greece, she is drawn to a woman she fancies as her doppelganger and a chase of sorts ensues as each woman pursues the other across Europe.

Best books from March/April

Where to start? Our March/April top-notch selection takes us from dystopian futures to new romance, spans centuries past and future, and sees magical realism sit happily alongside the gritty realities of a teenage girls’ boxing tournament.

Let’s just say it’s a knock-out.

Bullwinkel’s debut novel is set over two days of a teenage girls’ championship boxing tournament in Reno, Nevada, and puts you right there in the ring with the eight fighters slugging it out. Told as a series of linked stories from the point of view of each pair of boxers as the fight is underway, it gets into their minds, backstories and motivations, without ever losing the thrill of the action. Right at the top, for example, we learn that underdog and part-time lifeguard Andi Taylor is reeling from a boy dying on her watch at the pool. The wages she used to pay her fee to fight in this tournament, she notes, now ‘feels like blood money’. The novel’s prose as taut as the novel’s structure, with knock-out literary punches throughout. It may be early to call it, but this has to be one of the most dazzling debuts of the year.

It’s summer in the South of France and sisters Thea and Violet are spending the week in their father’s holiday home with half-brothers Luke and Conner, before their father – a busy international lawyer – flies in from China to join them. It’s the first time the four of them have spent any real time together and the unease in their dynamics as they struggle to get to know each other is palpable – especially between Thea and Conner, with their undercurrent of forbidden attraction. That, however, is soon to be the least of their worries. From the unidentifiable sound only Conner can hear to a plane that appears to drop from the sky, Andrew spins an elegantly unsettling web from the start. If there are inevitable echoes of Rumaan Alam’s masterful Leave The World Behind in its set-up, as it becomes increasingly clear that something very strange indeed is going on, Andrew’s dystopian tale takes on a vivid, haunting life of its own.

Cuban-born, Miami-based Ismael (‘Call me Izzy’) is making a living working as an unofficial Pitbull lookalike when he receives a cease-and-desist letter from the rapper’s legal team. His solution? To model his life on the star of another infamous Miamian – drug lord Tony Montana, aka Scarface, in the Al Pacino movie of the same name. This brings him to the attention of Lolita, a captive orca stolen from her pod decades before and now stuck in a tiny tank at Miami Seaquarium, going slowly mad with loneliness. Lolita sees something in Izzy – who lost his own mother during their perilous illegal crossing from Cuba to Miami when he was a child – and forms a psychic connection with him that serves as the second motor of what you may have already guessed is no straightforward plot. In lesser hands, this – not to mention the host of meta-narratives and divergences that Crucet throws on top – could have resulted in one big unholy mess. Crucet, however, is in charge at every step. A pacey, knowing, smartly insightful read that is laugh-out funny and desperately sad.

A woman returns to her home town, not to see her parents (she visits their graves ‘for the first time in 35 years’ on her way there), but to seek refuge in an austere monastery run by an order of nuns. She is disillusioned, it’s implied, by her work and her marriage, and while incredulous at the piety of the nuns and their routines (she doesn’t pray or believe in God herself), she finds a solace in the quiet that she returns to, eventually moving in with the order fulltime. That peace is disrupted, however, when a near-biblical plague of mice coincides with the return of the human remains of one of the order’s sisters from abroad. Overseeing their return is a ‘celebrity nun’ and activist from the town who our narrator went to school with, forcing her to reckon with unfaced truths from their entangled pasts as well as her own. Masterfully understated and all the more powerful for it.

The lives of 10 people living in and around Sheffield and Manchester cross and recross through a series of sexual encounters that range from joyous to transactional to downright troubling over the course of one long, hot summer. Recently separated Will kicks things off with a Tinder date with Manda, who is not impressed to learn he’s bisexual after they’ve had sex – an exchange that sets the scene for the various misunderstandings and misalignments that occur as each character takes charge of their story. Williams corrals a diverse cast – an artist, a sex worker, a drag queen and a welder among them – to create a fun, big-hearted and at times thought-provoking read about the search for connection in an all-too-busy, atomised world.

It’s 1843 and John Ferguson is a minister without a ministry. Sorely in need of the money he hopes will re-establish his congregation, he agrees to travel to a remote Scottish island to deliver the news that its remaining inhabitant, Ivor, must leave the home that has served his family for generations after its landowner decides to populate it with sheep (a practice in line with those of Scotland’s historic Highland clearances). When John suffers an accident, Ivor nurses him back to health, and the pair gradually build an understanding and connection over the days and weeks that follow. Back on the mainland, however, John’s wife Mary grows restless for her husband’s return and sets off on the long journey to bring him home. A profoundly intimate tale of loneliness, longing and the lengths you will go to for love.

‘If it weren’t for what happened later, everyone would have forgotten that night entirely,’ narrates mid-1980s emerging art star Anita de Monte of the night of her death (an incident that mirrors a notorious real-life event in the same year). The irony being that forgotten is exactly what Anita is by the time Puerto Rican-American art history student Raquel Toro stumbles on her story nearly 15 years later as part of her research into world-famous minimalist artist, Jack Martin – Anita’s husband – whose alleged involvement in his wife’s death has been carefully covered up. Set across dual timelines in which both so much and so little has changed, this is a smart, funny – and furious – shout out to agency, ownership and the female creative spirit in the face of art world hierarchies, hypocrisies and -isms.

This novel in three parts opens with what at first appears to be a gentle domestic scene, as father of twins Ayush announces his plan to swap out his children’s usual cosy bedtime story with a ‘surprise’ video. The video in question, however, quickly subverts what’s happening into something starker, darker and considerably more challenging, and serves as an arresting introduction into the subtly interlinked narratives that follow. Mukherjee isn’t setting out to tell us what to think, he’s telling us to think – about the lives we live and the impacts of the decisions we can all so easily and blithely make. A beautifully written and provocatively compelling tale of lives at the crossroads.

If it takes a bold writer to take on Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, it takes a brilliant writer to do it with the style, vigour and wit Everett brings to the story. James being, of course, Jim – the Black slave who runs away after learning he may be sold ‘down the river’ and ends up escaping on a raft with Huck. This, however, is Jim’s story first and foremost, not Huck’s, and Everett has a lot of fun playing with the tropes and expectations of the original (in this version, the language and speech patterns Jim and other Black slaves employ – so problematic to many contemporary readers – is a put-on for ‘white folks’ who ‘expect us to sound a certain way’). Following his Booker shortlist for The Trees in 2022 and current success of American Fiction, the Oscar-winning script for which was based on his 2001 novel, Erasure, Everett is on a much-deserved roll. James adds to that momentum brilliantly.

If you haven’t read Irish writer Mary Costello before, now’s the time – this is a writer so fully in control of her craft, she makes it look easy. Across its nine short stories entire histories are excavated and explored as family feuds, bitter marriages, lost dreams and more, quietly and desperately come to a head in settings as mundane as a car journey or mid-range hotel room. Costello’s prose remains coolly distant throughout, creating a dissonance that delivers its emotional insights and blows all the more powerfully. Just superb.

Beautifully observed debut set on an island off the Welsh coast in the late 1930s, where the arrival of a beached whale – shortly followed by two English strangers there to record its residents’ traditional ways before they’re lost forever – augurs ill to locals, not least because rumours of another looming war are beginning to swirl. To 18-year-old Manon, however, the strangers offer a promise of potential escape from the life she feels trapped within on the island. But these are dark and suspicious times, and things – including Manon’s new friends – are not entirely as they seem. A shimmering coming-of-age story.

Punk poetess and musician, Kyoko, is determined to avenge the death of her mother, Emi, by killing the man she holds responsible. The man in question – and sexual obsessive of the title, for his history of sleeping almost exclusively with Asian women – is middle-aged violinist Daniel. But as Kyoko’s foiled murder attempt turns into an increasingly hapless kidnapping, the truths and lies behind what really happened between Daniel and Emi – and, crucially, Alma, the beautiful, talented rising-star violinist Daniel was in a relationship with at the time – reveal more to all of their stories than first exposed. Prize-winning Korean American author Min’s posthumous novel is provocative, prescient and funny – it’s also a heartfelt tale of love.

With One Day bouncing back into the book charts on the back of the success of the current Netflix series, Nicholls’ latest novel reads rather pleasingly like a coda to its famous older sibling, albeit set over 10 days rather than two decades. It follows a pair of mismatched-on-paper (naturally) late-thirtysomethings – Marnie, a freelance copy editor, and recently separated geography teacher Michael, both of whom are desperately lonely – on an epic hike from one side of England to another with all the will-they-won’t-they tension Nicholls deploys so well. Does the course of love run smooth? Of course not – what would be the fun in that?

A notable novelist attends his playwright daughter Sophia’s first West End production with no knowledge that the story that’s about to unfold on stage is a deeply unflattering portrait of his behaviour on a holiday they shared in Italy a decade earlier. What follows is an astute, funny-sad analysis of power, perception and memory that questions the value of art and the responsibilities – and egos – of those who make it. Who, we’re left asking at its end, is the hypocrite now?

When artist and true-crime podcast obsessive Esther meets the wealthy, glamorous Naomi at an art dinner in New York, she baulks at Naomi’s suggestion that she takes on a glorified scrapbooking assignment she has planned as part of the celebrations for her husband’s forthcoming 60th birthday. Just days later, however, Esther’s world has fallen apart – her fiancé Jessica has left her and the only chance she has of holding onto the physical trappings of the life they’d built together means that scrapbooking for entitled billionaires will have to be done. Things get really interesting when Naomi dies mysteriously midway through the project. Henkel sets up the nod to Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl early on and as Esther’s obsession about what could have happened deepens, she gleefully riffs on its themes and tropes, sending Esther down a series of increasingly outlandish rabbit holes. Bonkers. In a good way.

This ambitious, three generation-spanning saga opens on the cusp of Y2K with Lily Chen – the daughter of Chinese refugees – feeling adrift. Recently graduated, she works as unpaid intern for an online magazine. It is not, she ruefully notes, the life her scientist parents imagined for her when they fled Mao’s cultural revolution in search of a better future. Meeting the handsome Matthew – a rich financier with an even richer family – changes all that and a fairy tale marriage follows. So why, when we meet Lily again several years later is she living alone with their son Nick on an isolated island estranged from Matthew and his family as well as her own? When Nick goes in search of his father, the truth he eventually uncovers is far wilder than any he might have imagined.

More March/April books in brief:

- The Children's Bach, Helen Garner: In her home country, Garner is recognised as one of Australia’s greatest living writers. This deceptively simple story of what happens when two old friends from university, Dexter and Elizabeth, are reunited by chance goes a long way to explaining why.

- Until August, Gabriel García Márquez: While far from his finest (García Márquez himself declared the story ‘didn’t work’), this posthumously published tale of a woman’s annual pilgrimage to place flowers on her mother’s grave and the one-night stands that follow, is an intriguing post-script to the great Gabo’s career.

- Day One, Abigail Dean: Dean’s follow-up to her best-selling debut, Girl A, explores the years-long fallout of a mass shooting in a Yorkshire primary school. As with Girl A, the chief focus is on the psychology and motivation of those involved rather than the horror of the event itself. A gripping read.

- The Morningside, Téa Obreht: Magical realism meets climate catastrophe in this latest novel from The Tiger’s Wife author. In a future world, the once prosperous Island City is now dependent on ‘climate refugees’ to attempt to repopulate it. Enter Sil and her mother, who move into the now seriously rundown, building of the title where, Sil soon learns, darkness resides.

- Meet Me When My Heart Stops, Becky Hunter: Emery is born with a rare illness that causes spontaneous heart failure. Each time it happens, she meets Nick, whose job is to guide people through their deaths. It’s an unusual premise for a love story, to which Hunter brings both plausibility and vulnerability. Heartbreakingly tender.

- Her Side Of The Story, Alba de Céspedes. First published in 1949 and reissued after renewed interest in de Céspedes brought praise from fans of both her writing and proudly feminist stance, including none other than Elena Ferrante (who writes the afterword in this edition), Her Side… is an epic tale of love and a woman’s search for independence and agency, set in fascist Italy. Brilliant.

Best books from January / February

Our Jan-to-Feb reads kick things off as we plan to continue with a brace of debuts by award-winning writers in their various other lives as poets and masters of the short story. Add to that a sprinkling of very different takes on pandemic fiction – a genre that doesn’t look like it’s going anywhere fast – some dark dystopian fiction from both sides of the pond, a visit to the Russian circus and an eerily beautiful Sami-Swedish novel in verse, and you have some idea of the diversity of reading fun that lies ahead.

Sigrid Nunez has form when it comes to populating her writing with animals – most famously in The Friend (in which a bereaved woman inherits a bereaved dog), which picked up the US National Book Award and brought Nunez to the wider audience she had long deserved. The animal in question this time is a macaw called Eureka, who our unnamed narrator is asked to house sit for in New York after his owners get locked down on the West Coast. She is later joined there by a young college dropout – the son of friends of the owners. If you hadn’t already guessed, it’s early 2020 – and we all know what that means. In many ways, then, this is a covid diary, and while Nunez captures the strangeness of that time, she is too good a writer for it to stop there, with musings on friendship, connection, writing, grief and the many vulnerabilities that are part and parcel of being alive.

Ever fancied running away to the circus? Then step right up. This tale of three Russian bar performers and the costume designer tasked with kitting them out for the competition of their lives takes you backstage and centre ring. Nathalie is between art college and her first job at a theatre company back in Belgium. Anna, the group’s star, has turned to circus after a failed sports career and is a relatively recent addition to Anton and Nino’s team, both of whom, we learn, are still reeling in their own ways from the near-fatal accident suffered by their previous flyer. They are all, in other words, in a period of life-changing transition. As the act comes together, trust between all parties gradually forms, and with it the ways in which each character – and Nathalie in particular – is ensnared by their pasts is revealed. Rich, immersive, psychologically astute – it’s a star performance all round.

Fans of surreal workplace dystopias in the vein of drama series Severance are well served in this scathing attack on the American dream-turned-nightmare. The Jonathan Abernathy in question – deeply in debt from student loans and being hounded for the debts of his deceased parents – is invited to become a ‘dream auditor’ for a firm hired by businesses to enter the subconscious minds of their white-collar workers and rid them of anything that might negatively impact on their productivity. For this, Jonathan will be released the brutal wheelhouse of endless repayments and – if he’s lucky – become a fully paid-up member of the capitalist machine. He attacks it with gusto but this does not, unsurprisingly, go well. As Jonathan’s dream life and real life begin to overlap ever more perplexingly, things get very dark indeed. Brutal, funny – and at its heart, deeply tender – this read is more than worthy of your hard-earned pay check.

This pacey, character-driven spin on US campus life forgoes the lecture hall to focus on a college dorm rooms and the myriad power struggles – financial, sexual, social – within. Set in a Southern university, it features the antics of five young women who share a dorm (three of whom for which money is no object), Millie, the live-in resident assistant overseeing them, and dreams of a home of her own, and visiting professor Agatha, who’s new to town, licking her wounds from an ill-fated romance and looking for her next writing project. If not quite as sharp as her exquisitely sharp debut, Such A Fun Age, its rat-a-tat pace and Reid’s keen ear for dialogue ensures a swallow-in-one-sitting read.

The acclaimed Irish short-story writer’s novel debut is a tale of grief, greed, desire and small-town rivalries – not only the feud between drug gangs that sets the narrative ball rolling with the kidnap of Doll, who’s being held for the alleged crimes of his older brother, but family, friends and co-workers too. Doll is delivered late at night to the isolated country house of misunderstood loner Dev – who is less than impressed by this development to his relatively benign involvement in local dealers the Ferdia brothers’ activities up until now. With Doll locked up in the basement and his girlfriend Nicky plotting with his family to get him back, all manner of dark comedy and chaos ensues. Essentially a study of manners and human behaviour dressed up as a crime novel, this rollicking tale is expertly and brilliantly told.

The queer Gen Z siblings of the title share a flat in central Auckland and a history of thwarted romance. Both are warm, witty, wry eccentrics who wear their hearts very firmly on their sleeves. Hapless TV host Valdin is in love with his ex – who now lives in South America – while English tutor Greta has fallen hard for a colleague who exploits that crush to her advantage. So yes, we have all the trappings of a very modern romcom, but it’s the pair’s relationships with and places within their complex, sprawling, loving Russian-Māori-Catalonian family that is the beating heart of their story, and this novel is all the richer for that. A huge hit when it was published in New Zealand, fingers crossed its considerable charms chime with an international audience – such success very much deserves repeating.

Subtly powerful tale of masculinity, memory and generational trauma set in a former mining town in northern England, as told through the lives of three generations of men. That’s brothers Brian and Alex, and the latter’s twentysomething drag artist son Simon in the main narrative, interwoven with a series of short, lyrical flashbacks to the siblings’ father in the days when the mine was still open. McMillan builds his story as carefully as the students who have descended on the town to do fieldwork for an academic study, unpicking Alex and Brian’s childhood to reveal its impact on their lives today. As Simon prepares for the genre-defying drag performance that he hopes will move him onto greater things, Alex is finally forced to confront a long-hidden truth. Quietly brilliant.

A single day broken into three parts (morning, afternoon and evening) across three years, from 2019 to 2021, Cunningham’s first novel in 10 years is a beautifully compassionate portrait of love and longing. The morning opens on Isabel, in Brooklyn, who is worried about work, her marriage to stalled rock musician Dan, her children and her beloved brother Robbie, who lives upstairs for now and with whom she projects her fantasies for an alternative, picture-perfect life in the form of a fake Instagram account headed up by the handsome, worldly ‘Wolfe’. However, the pandemic is coming and the walls are closing in, turning everything on its head. Stylishly told and beautifully – almost manneredly – written, Day is an exquisitely formed examination of the ever-shifting importance of bonds, how easily the threads between them can be pulled to breaking, and the beauty in what remains.

When Teddy’s father drives off a bridge on the anniversary of her sister’s disappearance 10 years previously, it reopens the decade-long wounds that first split her family apart. Determined to discover the truth behind both events, she turns sleuth, falling down the metaphorical rabbit hole of the title – both online, via various Reddit threads, and by bad decisions and becoming enmeshed in a host of dubious relationships in real life. While very much a thriller-style hunt for what happened, Brody’s debut is more accurately a sensitive, psychological investigation into the long-term, traumatic impact of lingering, unresolved grief.

Englishwoman in New York, Dylan, walks out of her successful advertising job, sublets her apartment and takes on a housesit for a stranger with vague plans to become a writer. From that beginning, she slowly but surely continues to dismantle her life, cheating on her long-distance boyfriend with married downstairs neighbour Gabe, blowing up friendships, and more. The story is set in 2015 – that now pivotal period, as Pountney notes, between Donald Trump’s decision not to renew his reality TV contract on The Apprentice and the announcement of his plan to run for office, and, back in Dylan’s UK homeland, when the proposal for what will become Brexit is on its second reading. Dylan is similarly ‘in between’. Question is, which way will she fall?

Lewis’s debut is being billed as one for fans of The Secret History and White Lotus. Please cast such comparisons from your head – if anything this thoughtful, intelligent and beautifully written exploration of fractured, dislocated souls shares more in common with Emma Cline’s 2023 release The Guest, insofar as it features an emotionally adrift, down-on-her-luck woman who takes up with a band of rich, young teenagers while trying to find her metaphorical way home. Said woman is thirtysomething Elen. Drinking heavily and now evicted from her home shortly after her husband left her, she’s adopted by four British teenagers who travel the globe on an endless skiing adventure dressed up as a hunt for utopia. Lewis is definitely a new talent to watch.