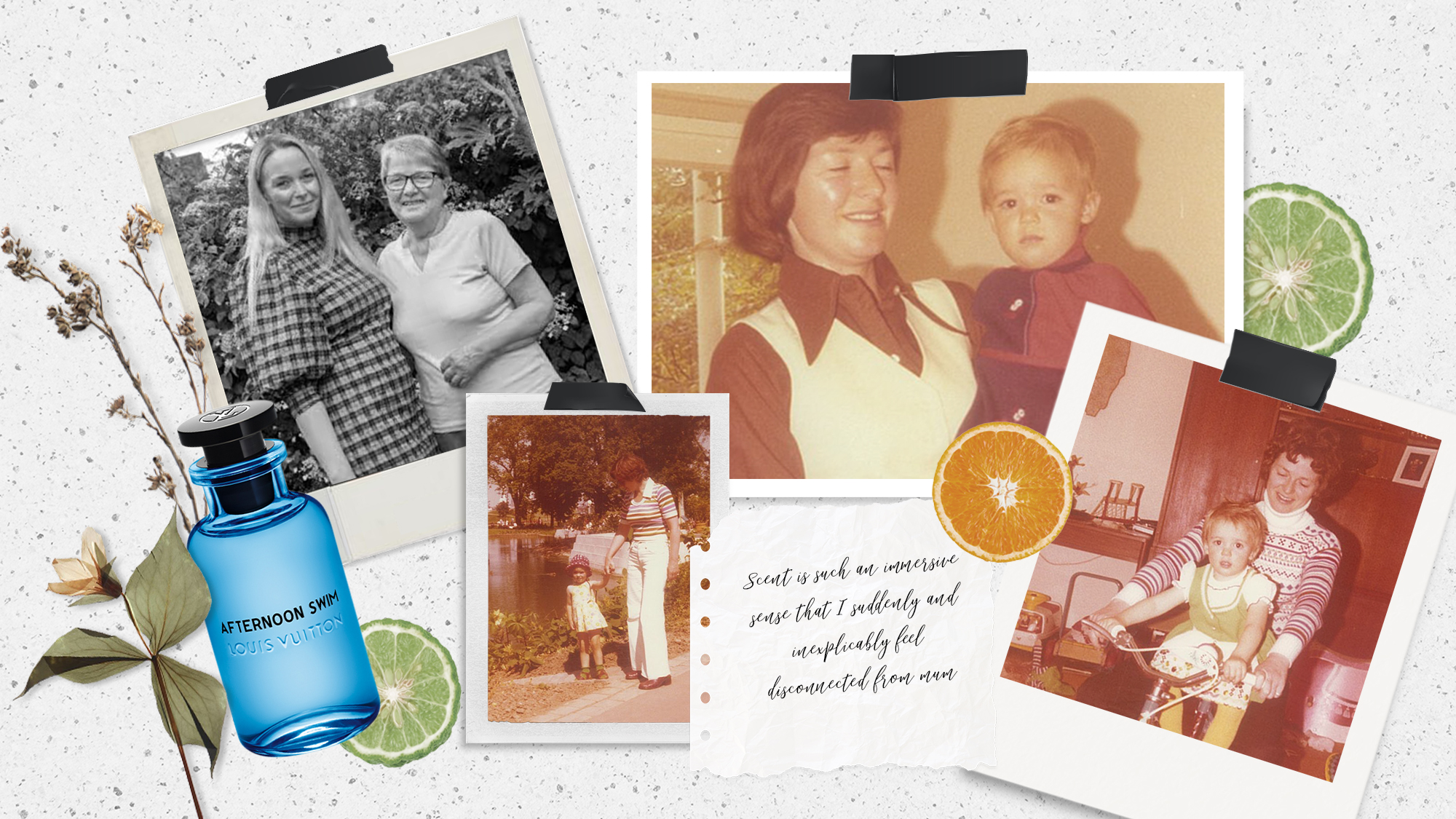

Cancer stole my mother’s scent

As we mark World Cancer Day on February 4, I'm paying tribute to my mum and the diagnosis that affected my relationship with her in an unimaginable way…

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

As we mark World Cancer Day on February 4, I'm paying tribute to my mum and the diagnosis that affected my relationship with her in an unimaginable way…

As the doors to the cancer ward swing open, the smell floods my nose, brazenly taunting me, a reminder of where I am.

It’s a cross between sweat and mothballs, that segues into the sweetness of overripe fruit, before fading to lemon floor cleaner.

I weave between the rows of beds eventually seeing mum’s tiny form huddled under the crisp bedsheets; their bright, fresh scent like a summer day.

The smell intensifies, as offensive as a swearing toddler, its innocent cheeriness at odds with the hospital surroundings. I want to scream, ‘How dare you?!’. I realise I can’t remember what it’s like to feel carefree and happy.

I kiss her forehead and that’s when it hits me. Mum is somehow different, sour and unfamiliar.

Cancer, as I later discover, can subtly alter a person’s natural scent. ‘What you smell are volatile organic compounds,’ explains Dr Mazhar Ajaz, a consultant oncologist at the Royal Surrey. ‘They are caused by cancer cells releasing substances through the pores that are different from those generated by healthy cells.’

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Bacteria living on the skin’s surface (known as the microbiome) are also affected.

‘There is a complex interplay between the immune-suppressing effects of the cancer, the therapy and microbiome,' adds Dr Ajaz. 'Cancer alters the natural population of the skin’s bacteria, changing its smell.’

Mum and I had been blissfully unaware of any of this in September 2018; the honeymoon period following the removal of a cancerous tumour from her breast.

Little did we know then that within three months she would be diagnosed with metastatic melanoma, a rogue cell having mutated so significantly that the disease had spread to her brain, lungs, liver and bones with the ferocity of a tsunami.

Her PET scan looked like the negative from a Polaroid; large black swathes revealed the devastation it left in its wake.

Put bluntly, my vivacious, utterly brilliant mum was dying. But I already knew that, long before the oncologist confirmed she had three months left to live without treatment. Wheelchair bound and barely weighing eight stone, she had lost all hope of recovery.

In a further blow, gone, too, was her natural smell – clean, creamy comfort and something that’s harder to identify but what you might imagine ‘soft’ to smell like, intermingled with her favourite Jo Malone Mimosa & Cardamom Cologne. DONE

In its place ‘eau de stage four skin cancer’ lolls unapologetically on her wrists, plus a metallic tang from the immunotherapy drugs routinely pumped into her veins.

Scent is such an immersive sense that I suddenly and inexplicably feel disconnected from mum; as though I am seeing her through frosted glass.

This is hardly surprising when you consider the role scent plays in our most primal experiences.

‘Scent-based bonding between mother and child occurs at birth,’ explains psychologist Suzy Reading. ‘The smell of the amniotic fluid, breastfeeding and skin-on-skin contact facilitates nourishment for the newborn, and cultivates care-giving behaviour in mothers. It also becomes how mother and child subconsciously identify each other.’

Perhaps this never stops and, even as adults, we rely on our mother’s innate smell to feel a sense of security, that we’re ‘at home’.

According to Johan Lundström, a neuroscientist at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, we subconsciously use smell to recognise those related to us. ‘There is a large genetic component to body odour,’ he says. ‘This biologically makes sense as we want to protect our own gene pool.’

As if proof were needed, a study by Wayne State University using sweaty T-shirts worn by 34 children, revealed that biological mothers were able to pick their child’s scent 27 times out of 30 (stepmothers were wrong five times out of seven).

Another by McGill University in Canada used neuroimaging. This creates pictures of the brain’s structure and neural activity to show that smelling the body odour of a close relative activates the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex – a part of the brain responsible for recognising family.

11 months down the treatment line, mum is responding well and, against all odds, a whisper of her natural smell is cutting through. I finally feel I am swimming up from the depths of a murky lake.

Ironically, while I’ve craved to smell my mum again, she has looked forward to wearing perfume. It breathes a vital message, she tells me. It says, ‘This scent is who I want to be.’

Perhaps it's why she chose Louis Vuitton's optimistic Afternoon Swim, which conjures up drinking fresh orange juice while walking along the beach.

For me, that wonderful new mishmash of scent – citrus and powdery skin – is like a slouchy jumper. It’s so comforting it virtually hugs me. I’ve created an entire imaginary world around it; one where cancer will never blight our lives again and where we enjoy a cadence of calm.

Only time will tell…

Fiona Embleton has been a beauty editor for over 10 years, writing and editing beauty copy and testing over 10,000 products. She has previously worked for magazines like Marie Claire, Stylist, Cosmopolitan and Women’s Health. Beauty journalism allowed her to marry up her first class degree in English Literature and Language (she’s a stickler for grammar and a self-confessed ingredients geek) with a passion for make-up and skincare, photography and catwalk trends.