Slaves for sale on phone apps: ‘I was offered a child as a domestic maid’

Selling people via an app is the shocking face of the modern-day slave trade, as Jess Kelly, director of the BBC’s Silicon Valley’s Online Slave Market discovered. Jess tells how her team broke all the usual rules of film-making when they discovered a petrified girl working as a ‘maid slave’, and ask what’s being done to control these apps

Selling people via an app is the shocking face of the modern-day slave trade, as Jess Kelly, director of the BBC’s Silicon Valley’s Online Slave Market discovered. Jess tells how her team broke all the usual rules of film-making when they discovered a petrified girl working as a ‘maid slave’, and ask what’s being done to control these apps

Words by Jess Kelly

‘Look, this is Daddy and Mummy,’ says the Kuwaiti woman, gesturing to our undercover ‘husband and wife’ team as she tries to explain to her maid that she’s about to be sold to new owners. Fatou is a 16-year-old girl from Guinea, West Africa and she can be ours for £2,9370.

Turning to ‘Mariam’ and ‘Omar’, who are posing as newlyweds in the market for a maid, she continues touting the merits of the Guinean child sitting silently by her side: ‘she’s got a pleasant face, she’s kind, she won’t say no.’

When asked how old she was her seller replies, ‘Shall I tell you the truth? For my sake, she’s 16. The papers say one thing, but they changed them in Guinea so she could work. And she’s an orphan, no mother or father, nobody except her grandmother.’ The woman presses our team to buy her quickly, ‘When will you take her, God willing? It’s just we want her to move on quickly so we can get another maid.’

Insta slave market

This exchange happened while we were undercover in Kuwait for BBC News Arabic investigating reports of domestic workers being sold on mobile phone apps like Instagram and the Kuwaiti app, 4sale, in a burgeoning trade criticised by Urmila Bhoola, UN Special Rapporteur, Contemporary Forms of Slavery. ‘This is the quintessential example of modern slavery,’ she told BBC News Arabic.

There are roughly 700,000 domestic workers in Kuwait - at least one for every two citizens and despite the relatively strong laws in place to protect them, many are routinely abused and exploited. And it seems Google, Apple and Facebook-owned Instagram are enabling an illegal online slave market by approving and providing apps used for selling domestic workers in the Gulf.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

We spent a week secretly filming a dozen meetings with people breaking the law trying to sell us their domestic worker. But meeting ‘Fatou’ (her name has been changed for her protection), represented a disturbing turning point.

Watching the footage back in my hotel room, I felt queasy. The girl looked so young. She was so powerless. She could grow old in this situation, never having a chance to do anything she wants. Fatou had been there for nine months. It’s rare as documentary filmmakers to intervene in your subjects’ lives, but in this case we had to. This was a child being put up for sale on an online slave market, exposed to many potential abuses and cut off from the world. But for her safety we needed to approach the situation very carefully - in Kuwait reporting domestic workers to the authorities can be risky as they often side with the employer and domestic workers end up being jailed.

With the help of a local NGO that fights for the rights of domestic workers and after exhausting all their means to contact or locate Fatou, we took our evidence to the Kuwaiti authorities. The Domestic Workers Office was happy to assist. Ten days later Fatou was found. She was registered as underage and deported back to Guinea.

Fatou’s new life

After she landed, we tried to stay in touch with her via Facebook, but soon she went offline and we lost her again. After three anxious weeks, a journalist-friend found her sick with malaria and sleeping on the floor of a distant relative’s house in Conakry, the capital of Guinea. We travelled to meet her. She was now living with a woman from a local NGO who had decided to adopt her. Giggly and teenager-like, her hair adorned with silver beads, she was transformed.

I was worried about showing her our footage of her being offered to us for sale, in case she felt violated, but she watched it calmly and said: ‘If I had the opportunity to talk to this lady, I would tell her that she’s wearing Muslim dress, but she’s not Muslim, because Muslims wouldn’t act like that.’ Fatou asked if she could show the video to her grandmother, explaining that nobody in Guinea believed what had happened to her.

Fatou was in 8th grade when she left for Kuwait, she should have been preparing for the Guinean equivalent of GCSEs. She had no real parents - her mother had died in childbirth and her father lived in the distant forest regions of the country, she’d only met him once. Her grandmother who had brought her up couldn’t afford to take care of her anymore and so her family took up the offer of a Guinean couple to forge her passport to make her eight years older than she really was, and send her abroad to work as a nanny. It wasn’t until Fatou was on the plane that she realised she was being sent to Kuwait, ‘I thought I was going to China… A girl I knew had gone to work in Kuwait and came back pregnant, neither me nor my grandmother would ever have accepted me going to Kuwait.’

Life as a slave

Fatou landed into a nightmare. In her first job in Kuwait she worked for a husband and wife for six months without payment. 'They took my passport and my phone. I was the one doing all the chores in the house: laundry, cleaning, cooking the rice, and all. I worked from 6am to 1am. There was never a day off. I couldn’t cope. Sometimes I used to cry while working as it was too much for me. I was crying all the time and not eating.'

Permits for domestic workers in the Gulf are attached to their employer. Once the employers have paid an agency for the permit the domestic worker cannot quit their job or leave the country without the employer’s permission. But apps like ‘4Sale’ and Instagram have created a black market where the permit - and the person - can be resold for profit.

After six months without payment, Fatou refused to work and demanded the family take her back to the agency they had got her from. After three days, they did - but they never paid her any wages.

With no money and her mobile phone confiscated, she was unable to get a message out to her grandmother back in Guinea, and with no say in the matter she was immediately transferred. The new family wasn’t any better. Aside from all the daily chores, she was also expected to look after ten children. She refused to work and asked her new ‘madam’ to take her back to the agency. It was a bold move.

The ‘madam’ refused, and instead gave her an ultimatum, either her family in Guinea sends her the full amount she paid for her, or she would sell her on to another family. ‘I told her: I haven’t sent even 100 Guinean Francs [£1] back to my family, how could they reimburse her?’

Realising that she couldn't extort any money directly from Fatou and her family, the ‘madam’ decided to post an ad on '4Sale', something she admitted doing many times before to our undercover team. '4Sale' is the most popular commodity app in Kuwait, alongside used cars and TVs there's a dedicated section where you can buy and sell a domestic worker. The ad read: ‘African from Ghana good at cleaning and house chores. 1,150 KD (£2,930).’

When our husband and wife undercover team called the seller, she lied and said that the girl was 20-years-old. She described her as ‘very good and smiley’ and told us, ‘I don’t let her out alone, no, no, no.’

Fatou suffered more than we had guessed when she was being offered to us for sale. She told us the son of one of her employers had beaten her. ‘Whenever he found me sitting down to eat, he would tell me to stop and clean his shoes or do some other kind of job. If I refused he would hit me or take something and throw it at me. They would also swear at me in Arabic saying, ‘Hey animal, hey piece of shit!’ Sometimes they would deprive me of food.’

‘I feel like I’m coming back from slavery,’ she said and explained how difficult it is to extract herself from that situation. ‘There is nothing you can do, you haven’t got anybody there, no mum or dad. I was scared that if I tried to run away they would send me to the police.’ Despite working for nine months in Kuwait she was only paid two month’s salary and that went straight to her Guinean traffickers.

Fatou is now going back to school and living with her adopted family. ‘I’ve found happiness and freedom. I can only pray that people still there come out in peace.’

One of the challenges in making this film was establishing whether this online trade could be defined as modern slavery. Fatou became the quintessential example of why it could be: she was not paid, her passport was confiscated, she was isolated from the outside world by not being allowed a phone or to leave the house alone - all of these are indicators of forced labour and human trafficking under the International Labour Organisation‘s (ILO) definition of modern slavery.

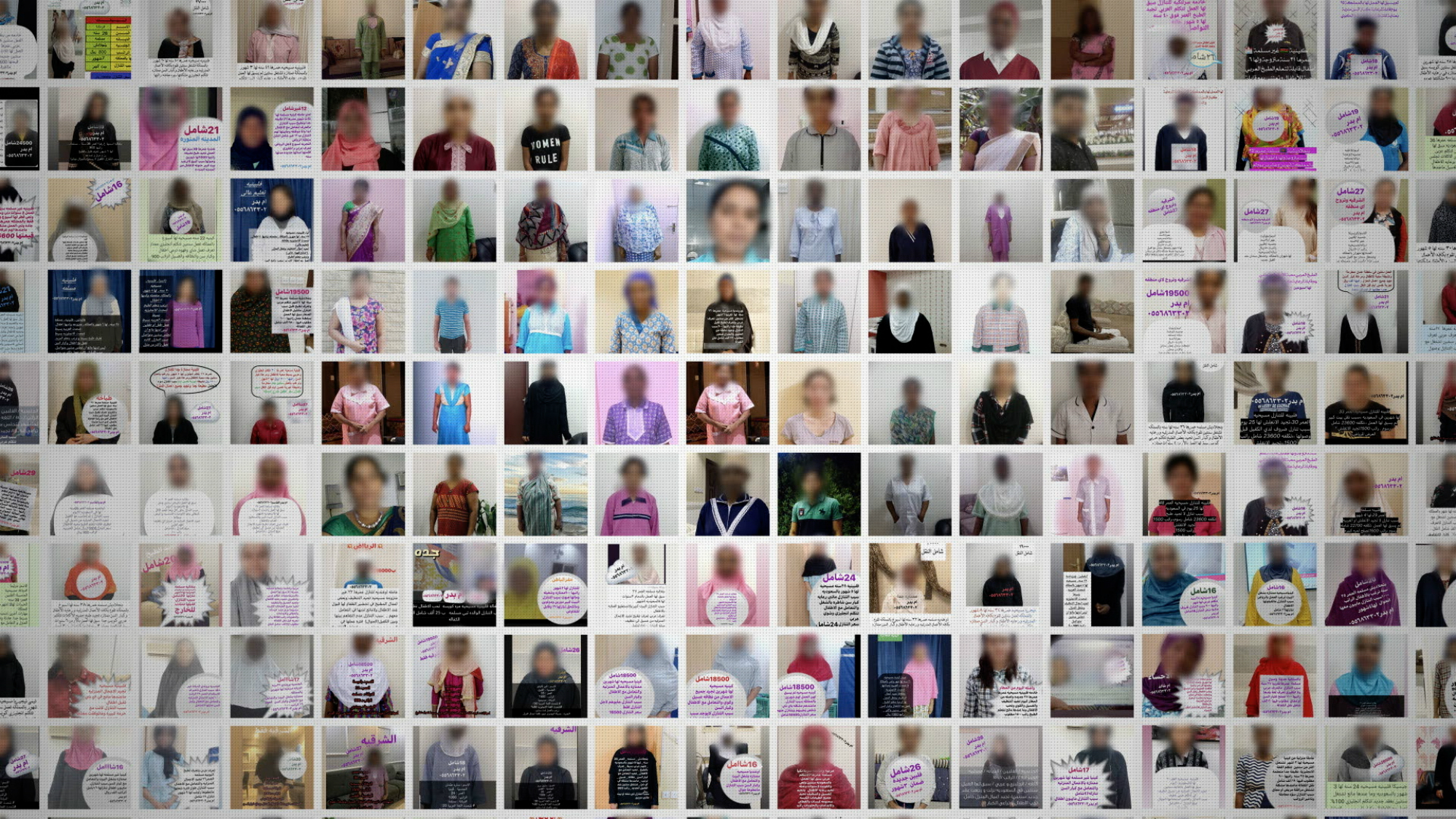

And these practices are very common: in our week in Kuwait, we spoke to 57 sellers in total. In all the cases, the sellers were open about depriving ‘their’ domestic workers of at least one of their basic human rights. But more fundamentally, they were selling these women without their consent, posting their photographs without their knowledge alongside details about their marital status, religion, ethnicity, or skin colour - and selling them into a situation they had no control over.

Justice for Fatou

A leading US human rights lawyer, Kimberley Motley has decided to take on Fatou’s case. She wants to see charges brought against the woman who tried to sell us the 16-year-old. Under Kuwaiti law anyone who employs a domestic worker under the age of 21 can face up to six months in prison and pay a large fine.

Motley also wants to seek compensation for Fatou from the tech companies that enable the apps that facilitate modern slavery, Apple proclaim that they are responsible for everything that's put on their App Store. And so our question is, what does that responsibility mean?But any resolution lies far in the distance.

But there are still thousands of domestic workers being bought and sold on Instagram, Haraj and other apps available on Google Play and the Apple App Store. Following our investigation 4Sale has removed its domestic workers section and told us it would cooperate with the authorities. Facebook said it has removed the hashtag, maids for sale, from Instagram and closed hundreds of accounts. The Kuwaiti government also took action to remove hundreds of accounts they found online after the investigation. But they declined to comment further on Fatou’s case.

Both Google and Apple told the BBC that this type of behaviour has no place on their application stores.

* Watch the full documentary of BBC News Arabic Silicon Valley Online Slave Market on the BBC YouTube channel

* Support Kimberley Motley’s legal campaign ‘Justice For Fatou, the girl sold online’ at: https://www.gofundme.com/f/justice-for-fatou-the-girl-sold-online

Maria Coole is a contributing editor on Marie Claire.

Hello Marie Claire readers – you have reached your daily destination. I really hope you’re enjoying our reads and I'm very interested to know what you shared, liked and didn’t like (gah, it happens) by emailing me at: maria.coole@freelance.ti-media.com

But if you fancy finding out who you’re venting to then let me tell you I’m the one on the team that remembers the Spice Girls the first time round. I confidently predicted they’d be a one-hit wonder in the pages of Bliss magazine where I was deputy editor through the second half of the 90s. Having soundly killed any career ambitions in music journalism I’ve managed to keep myself in glow-boosting moisturisers and theatre tickets with a centuries-spanning career in journalism.

Yes, predating t’internet, when 'I’ll fax you' was grunted down a phone with a cord attached to it; when Glastonbury was still accessible by casually going under or over a flimsy fence; when gatecrashing a Foo Fighters aftershow party was easy-peasy-lemon-squeezy and tapping Dave Grohl on the shoulder was... oh sorry I like to ramble.

Originally born and bred in that there Welsh seaside town kindly given a new lease of life by Gavin & Stacey, I started out as a junior writer for the Girl Guides and eventually earned enough Brownie points to move on and have a blast as deputy editor of Bliss, New Woman and editor of People newspaper magazine. I was on the launch team of Look in 2007 - where I stuck around as deputy editor and acting editor for almost ten years - shaping a magazine and website at the forefront of body positivity, mental wellbeing and empowering features. More recently, I’ve been Closer executive editor, assistant editor at the Financial Times’s How To Spend It (yes thanks, no probs with that life skill) and now I’m making my inner fangirl’s dream come true by working on this agenda-setting brand, the one that inspired me to become a journalist when Marie Claire launched back in 1988.

I’m a theatre addict, lover of Marvel franchises, most hard cheeses, all types of trees, half-price Itsu, cats, Dr Who, cherry tomatoes, Curly-Wurly, cats, blueberries, cats, boiled eggs, cats, maxi dresses, cats, Adidas shelltops, cats and their kittens. I’ve never knowingly operated any household white goods and once served Ripples as a main course. And finally, always remember what the late great Nora Ephron said, ‘Everything is copy.’