A Frida Kahlo exhibition has come to London and we're here for it

Her vibrant self-portraits often reflected a life of pain, her stormy marriage and strong political views. Now, 60 years after the artist's death, she continues to inspire and shock in equal measures

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Here's everything you need to know from how to get tickets to the woman behind the exhibition...

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo is an icon, with a colourful and compelling life story, but having died in 1954, most of what we learn about her is from books and films, with Salma Hayek nominated for an academy award for portraying her in Frida.

Now however, we will be able to see for ourselves as a brand new exhibition has come to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, showcasing Frida's most intimate personal belongings - from artefacts to clothing.

Introducing: Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up

Locked away for 50 years after her death, this collection has never before been exhibited outside Mexico - and it's set to give us a fresh perspective on her incredible life story.

What is in the Frida Kahlo exhibition?

Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up will present some of Frida's most intimate personal belongings, with the highlights including a Guatemalan cotton coat with Mazatec huipil belonging to the artist, a selection of Frida's cosmetics and the prosthetic leg with a leather boot that she used to wear.

When is the Frida Kahlo exhibition?

The Frida Kahlo exhibition is running from Saturday 16th June till Saturday 4th November so we should all be able to get tickets.

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

How can I get tickets for the Frida Kahlo exhibition?

Tickets for Frida Kahlo: Making Her Self Up can be purchased either on the door of the V&A or online - and cost £15 each. It is recommended that you book in advance via their website though, with the exhibition set to be very popular.

What is Frida Kahlo's life story?

With a sickening crash, the bus collided with a trolley car on a packed street in Mexico City. It was 17 September 1925, and as passengers were flung helplessly from the wreckage, an iron handrail pierced 18-year-old Frida Kahlo’s abdomen, fracturing her spine and shattering her pelvis. Her collarbone was broken, her right leg – already withered from childhood polio – was fractured in 11 places and her foot dislocated. Frida’s boyfriend at the time, Alejandro Gomez Arias (known as Alex), was travelling with her and remembers the scene: ‘Someone in the bus had been carrying a packet of powdered gold, which fell all over Frida. When people saw her they cried, "La bailarina!" With the gold on her red, bloody body, they thought she was a dancer.’

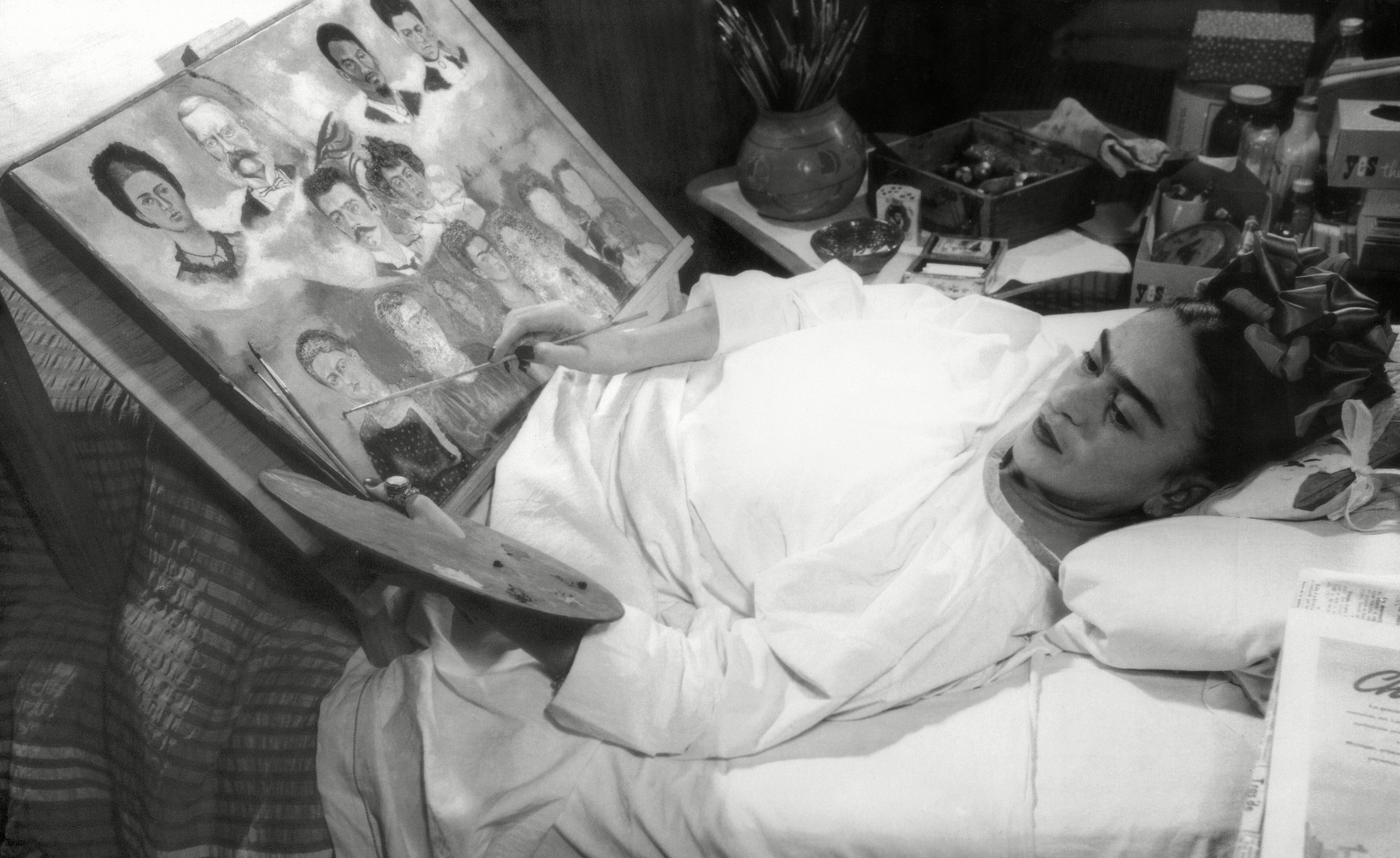

The physical, emotional and psychological impact was devastating. Frida was encased in a full-body cast for three months and underwent more than 30 operations. ‘She lived dying,’ said a close friend. But she found a way to communicate her fear and desperation through her uncompromising art. In 1926, confined to bed after a relapse, Frida was given an easel and paints by her parents. In the 29 years between her accident and her death in 1954, aged 47, she would create sensual, disturbing, powerful art, many self-portraits that challenged convention, pre-dating Tracey Emin’s artistic self-exposure by decades. ‘I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best,’ Frida said.

Born on 6 July 1907 in Coyoac·n, a suburb of Mexico City, Frida later made a political gesture by claiming her birth date was 1910, so her life would begin with the Mexican Revolution. Raised with three sisters by their German father Guillermo, a photographer, and mother Matilde, Frida’s upbringing was unconventional. At six, she contracted polio, spending nine months confined to bed. Against the odds, eight years later she was one of only 35 girls in Mexico City to attend an elite prep school. A natural-born rebel, Frida would let off firecrackers in class and wear men’s clothing to taunt visiting artists. One visitor was world-famous painter Diego Rivera, who was invited to paint a mural in the school’s amphitheatre in 1922. He was 36 and Frida just 15, but she declared: ‘My ambition is to have a child by Diego Rivera.’

The pair met again at a party six years later and, despite becoming known as something of an odd couple – her parents called them ‘the elephant and the dove’ (he was immensely overweight) – they married in 1929. He built them adjacent houses, joined by a bridge, and Frida would lock the connecting door when she was angry with him, usually over one of his many affairs. ‘She never got used to his loves,’ remembers her friend Ella Wolfe. ‘Diego never cared. He said having sex was like urinating. He couldn’t understand why people took it so seriously.’

The affair that caused Frida most pain was Diego’s relationship with her beloved younger sister, Cristina, in 1934. Frida described feeling as though she was being ‘murdered by life’ in her painting A Few Small Nips, which is also based on a newspaper account of a woman stabbed by her boyfriend. For a short time, Frida moved out. ‘I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. The other accident is Diego.’

Openly bisexual, Frida also had extra-marital relationships with both women (which Diego encouraged) and men (which enraged him). Despite their difficulties, they were compulsively drawn to one another. Frida suffered multiple miscarriages and a medically advised abortion as she tried and failed to have Diego’s child, as a result of her pelvic injuries from the bus accident. She portrayed her pain in her painting Henry Ford Hospital, which shows her lying on blood-soaked sheets after a miscarriage. ‘Never before has a woman put such agonised poetry on canvas,’ said her husband at the time. Together, the couple became the centre of art, culture and Marxist politics in 30s Mexico.

In 1937, Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and his wife came to live at Frida’s family home, Casa Azul, for two years, after he had been expelled from his country by Stalin. Trotsky and Frida had an impassioned affair (she called him ‘el viejo’, old man, and he would leave her love notes inside books he loaned her). In Frida’s famous self-portrait Between The Curtains, she is holding a document that says, ‘To Trotsky with great affection, I dedicate this painting November 7, 1937. Frida Kahlo, in San Angel, Mexico.’ Two years later, both she and Diego were suspected, but cleared, of involvement in Trotsky’s assassination.

Meanwhile, Frida’s reputation as an artist was growing. In 1938, she was invited to exhibit her work in New York; artist Georgia O’Keefe came to the opening and Hollywood actor Edward G Robinson bought four of her works. ‘She became one of a group of post-revolutionary intellectuals who reinvented traditional culture through a lens of modernity,’ says Adriana Zavala, curator of a new exhibition of Frida’s work that opens at The New York Botanical Garden in May.

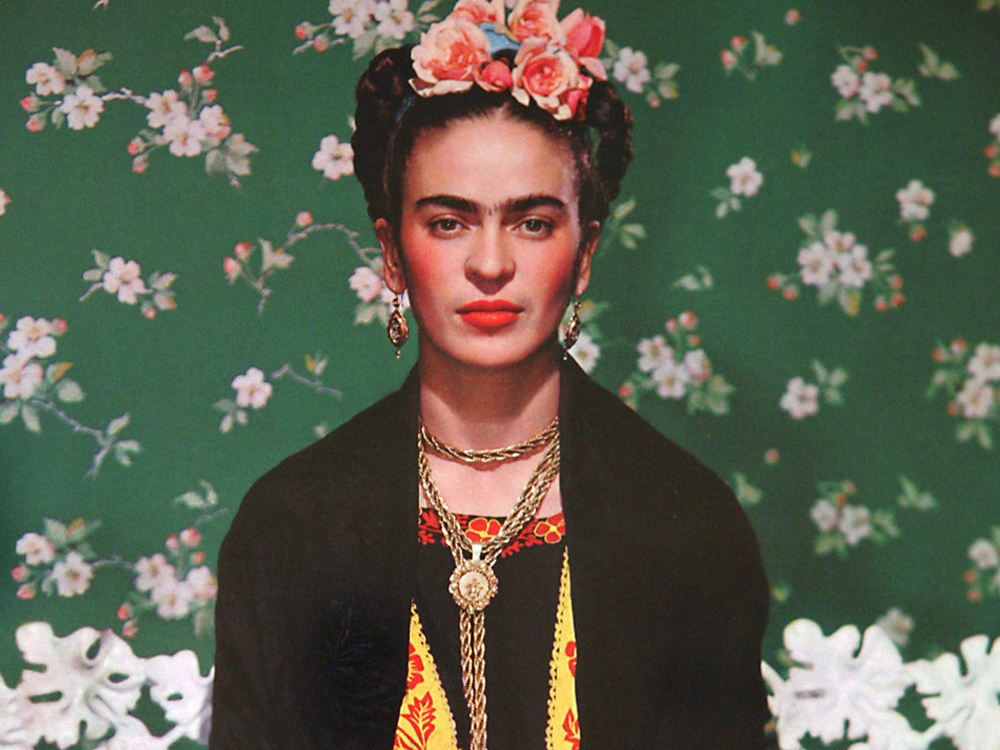

Known for her exotic outfits, Frida adopted the traditional costume of Mexico’s Tehuana Indians, with ribbons in her hair. She sometimes wore gold and diamond tooth caps that glittered when she smiled. Refusing to conform to feminine beauty ideals, she would blacken her faint moustache and heavy eyebrows to exaggerate them. When she walked down the streets, children would mob her and ask where the circus was. Her mother had dressed in Indian costume as a child and Frida originally began wearing the full skirts to disguise her withered leg. ‘Indigenous culture was adopted by Mexican intellectuals and Communists to signal their support of native practices,’ explains Zavala. ‘But Frida’s way of dressing was so extreme, it was a form of aggression; she was asserting her will to be different and to flout convention.’

Her compelling image is still resonant today. Madonna said last year that when she was a struggling dancer in New York: ‘I would look at a postcard of Frida Kahlo taped to my wall, and the sight of her moustache consoled me. Because she was an artist who didn’t care what people thought.’ Even the latest Valentino Resort collection was inspired by Frida’s look. ‘We are fascinated by a character able to live following her own schemes and rules, not subjected to any kind of protocol,’ said joint creative director for the label, Pierpaolo Piccioli.

Frida showcased this independent attitude in Paris in 1939, when she was invited by Andre Breton to show her work. Unwell with a kidney infection, she was missing Diego and reportedly hated the ‘artistic bitches’ of the city’s bohemian cafe society. Nevertheless, her time in Paris was a triumph. Elsa Schiaparelli designed a dress inspired by her, the Louvre bought one of her paintings – its first by a 20th-century Mexican artist – and she even helped 400 refugees from the Spanish Civil War escape to Mexico. ‘They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t,’ she said at the time. ‘I never painted my dreams. I painted my own reality.’

Back in Mexico, that reality was to become even harsher. After five months apart, Frida and Diego’s marriage was over – he claimed he ended it to avoid causing her more pain with his infidelities. ‘I understood that for him it is better to leave me. Now I feel so rotten and lonely,’ she wrote at the time. But Diego couldn’t live without her, either. A year later, they remarried, with conditions – Frida insisted on supporting herself and refused to have sex with her husband.

Their uneasy reconciliation coincided with Frida’s deteriorating health. From 1944 until her death, she suffered repeated operations on her spine – another consequence of her accident – spending 28 months encased in a plaster corset, sometimes suspended from iron hoops in the ceiling, or with sandbags attached to straighten her back. In 1953, in Mexico, she appeared at her final exhibition, in a huge four-poster bed decorated with skeletons and pictures of her friends, family and Diego. ‘I am not sick. I am broken,’ she said. ‘But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.’

Eventually, she was diagnosed with gangrene and her leg was amputated from the knee. Frida, who had occasionally used drink and drugs to cope with the agony of her condition, became even more dependent on them – sometimes drinking two litres of cognac a day and injecting a cocktail of opiates. She tried hard to maintain the Frida persona, wearing red leather boots with gold embroidery and bells to disguise her prosthetic limb, but her depression and despair were obvious. ‘If I were brave, I would kill her. I cannot stand to see her suffer so,’ lamented Diego.

She died in 1954 – whether from suicide or natural causes is still a mystery – but her passing was characteristically macabre. At her cremation, the intense heat of the furnace caused her body to sit up and her hair flame around her head ‘like a sunflower’. The shape of Frida’s body was apparent for a few moments in the ashes. The young girl who had been covered in gold dust was now a silvery skeleton.

Today, Frida remains the world’s most recognised female artist, according to Zavala. ‘There’s a very powerful self-presence in her paintings, but her work isn’t purely biographical: it reflects the politics and environment of her times and that has influenced generations of artists and feminists ever since.’ As Frida herself once said: ‘I used to think I was the strangest person in the world, but then I thought there must be someone who feels bizarre and flawed in the same ways I do. Well, I hope that if you are out there and read this, yes, it’s true, I’m here, and I’m just as strange as you.’

The Frida Kahlo exhibition will be open at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, from Saturday 16 June 2018 to Sunday 4 November 2018.

Jenny Proudfoot is an award-winning journalist, specialising in lifestyle, culture, entertainment, international development and politics. After working at Marie Claire UK for seven years - rising from intern to Features Editor - she is now a freelance contributor to the News and Features section.

In 2021, Jenny was named as a winner on the PPA's '30 under 30' list, and was also listed as a rising star in journalism.