“It’s Not All Gold Medals and Trophies”: What It’s Really Like Being a Top Female Athlete in 2025

Female athletes are more likely to report anxiety, depression, distress, and disordered eating than their male counterparts - but these women are determined to change the narrative.

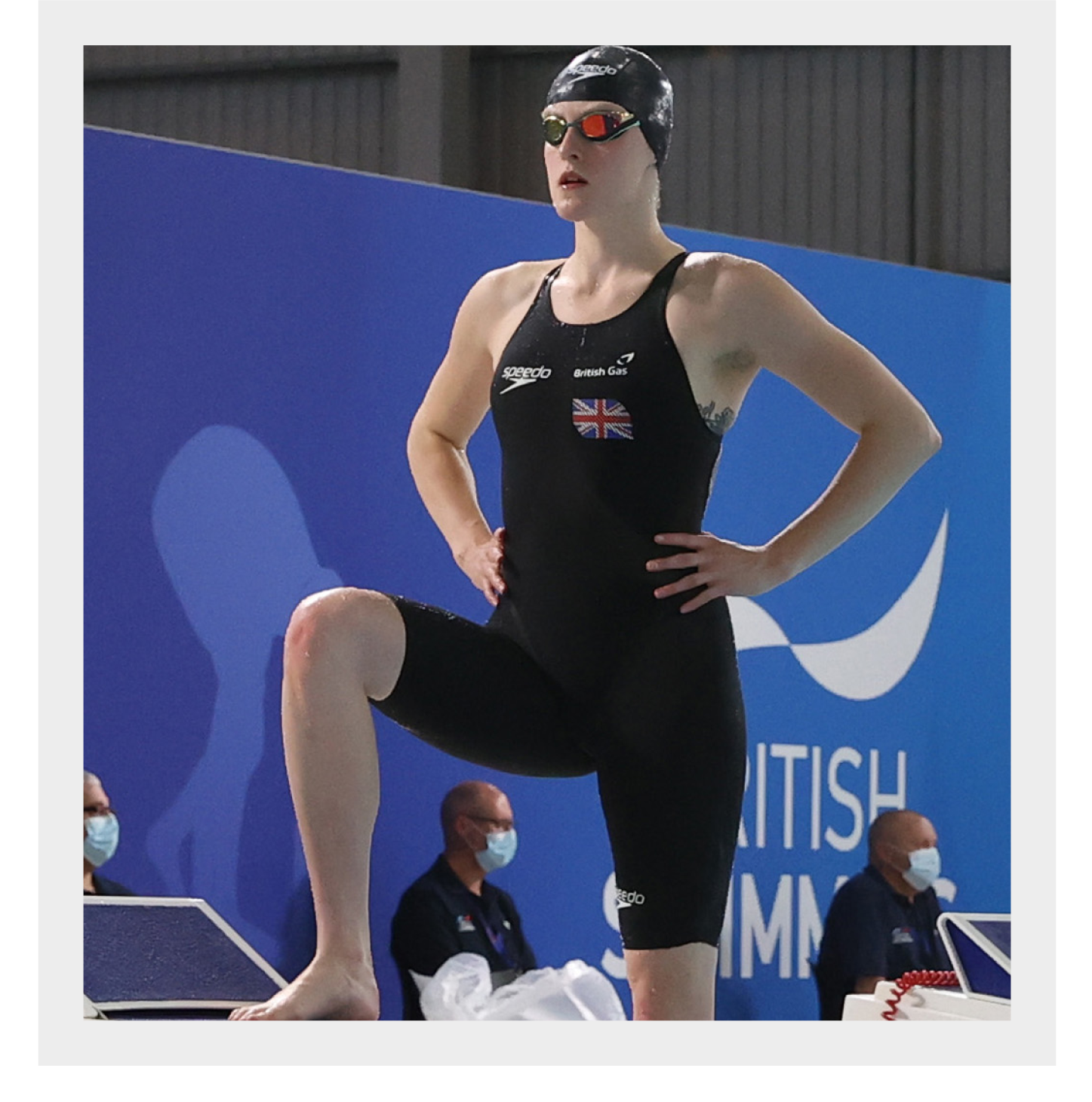

Growing up in Nottingham, Amber Keegan was swimming from a young age. She always loved the water - it was her safe space and a place of solitude and calm. Her talent for the sport was clear, too, and she’d competed at the World Junior Championships and placed at the European Junior Championships at the age of just sixteen.

But it wasn’t all gold medals and trophies. For many years, she battled debilitating mental health struggles that threatened to end her career and sabotage her dreams of making the Team GB Olympic squad.

“I started struggling with an eating disorder around 2016,” she shares exclusively with MC UK. “I was eating less and exercising more, trying to control the parts of my brain that were spiralling.”

By her own admission, it was a warped survival mechanism - but she felt there was no escaping the harmful perceptions and stereotypes around sportswomen on TV. “Women were supposed to look petite, not strong, supposed to be slender, not broad-shouldered, and supposed to eat less than our male counterparts, not more. I didn’t realise how much all of these messages were ingrained in me and adversely affecting my health,” she admits.

Only after she’d made a full recovery did she realise how much her mental health had been impacting her performance. “I was tired more, in pain more, less resilient and less able to take feedback,” she reflects.

Keegan went on to swim at two World Championships, win international open water races, and swim the English Channel in 8 hours and 44 minutes - none of which she feels would have been possible without the level of care she was given during her recovery. “I was lucky to have a support team who focused on me as a person and not an athlete - there was no being dropped from my club or anything like that, rather, they focused on me as a person and as a human,” she reflects. “Because of that, it gave me the space and time to make a full recovery.”

Nine years on, her life looks a little different. Driven by her own experiences and a desire to reshape the conversation around mental health for female athletes, she launched Athlete Interactions, a charity aimed at ensuring her peers never feel as alone as she once did. Since 2021, the non-profit has fostered a safe, open community where girls and women can share their experiences and access the support needed, being awarded a P&G Athletes for Good grant in 2024.

Women were supposed to look petite, not strong, supposed to be slender, not broad-shouldered, and supposed to eat less than our male counterparts, not more.

Wondering why organisations like Athlete Interactions are needed? Sadly, there’s a wealth of research that indicates that female athletes experience higher rates of mental health challenges than their male counterparts. Studies published in Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil., SportsAid, and others highlight an insider secret within the sporting world - that female athletes suffer with mental health issues more than men, experiencing higher rates of anxiety, depression, disordered eating, and body image issues.

Women are 30% more likely to be subjected to online abuse than their male counterparts, and 39% say body image is one of the main causes of their anxiety, compared to just 12% of sportsmen.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, sports inequities, violence, abuse, family planning challenges and hormonal fluctuations all play a part, too, with female athletes also reporting feeling an immense amount of pressure to succeed, alongside higher rates of scrutiny from coaches, peers, and the public.

A large challenge which female athletes have to navigate is childbirth, including the difficulty of returning to sport post-childbirth and the loss of identity that can sometimes follow.

Below, we chat to three female athletes about their own mental health journeys, plus a top expert in her field about what more needs to be done to give women the support they deserve. TLDR: If women were better supported, could they perform at a higher standard? And further, could it finally level the playing field?

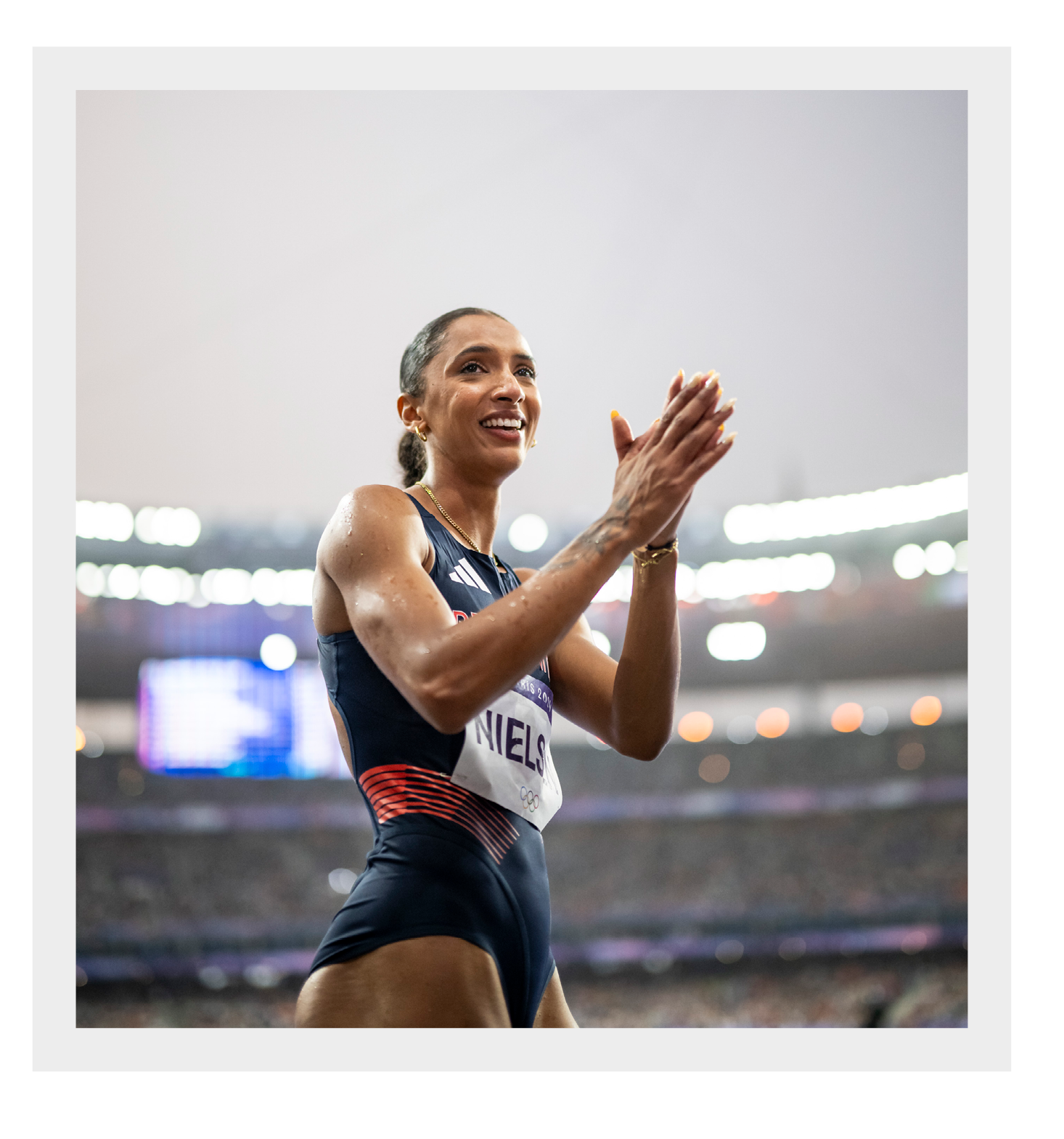

Laviai Nielsen, Team GB Olympic Bronze medal 400m sprinter

Laviai Nielsen, Team GB Olympic Bronze medal 400m sprinter and former MC UK cover star

“I’ve been a professional athlete for over a decade now, and I’ve definitely seen a real shift in how female athletes are perceived. Coming off the back of Paris 2024, where we had more women representing Team GB than men, it feels like we’re finally being recognised for our strength, resilience, and presence, not just in competition, but in conversation.”

“It felt as though people were interested in sportswomen’s stories and journeys, and I felt so proud to be a part of this era. In saying that, as far as we’ve come, I do also feel like there’s a long way to go. Women in sport are still significantly underpaid compared to men. A 2023 report from Forbes revealed that only two women are ranked in the top 50 highest-paid athletes globally. We’re still fighting for visibility, equal opportunities, and financial equity, and while progress is happening, I think we’re still at the beginning of this journey.”

“We always say that the highs in sport are so high, they’re almost euphoric. They make all the hard training and tough days worth it. But at the same time, the lows are incredibly low. When you decide to become a sportsperson, you pour everything into this life; your time, your energy, your identity. So when things don’t go to plan, or you fall short of a goal, it can rock you to your core.”

“You begin to question everything, including your identity and what brings you happiness. Add to that the pressures of being a woman in sport - whether it’s conversations around family planning, dealing with health issues, hormonal fluctuations, or body image scrutiny - they can all lead to poor mental health.”

“After major events like the Olympics, I’ve seen so many athletes, myself included, question their identity, their motivation, and even their future. Without strong support systems in place, that post-Olympic crash can spiral. And the tough truth is that mental health and performance are intertwined. If you're not okay mentally, your physical performance suffers, which only fuels those negative thoughts. It can end up being a dangerous cycle that needs breaking before it breaks us.”

“I’ve experienced trolling or negativity on my social posts, especially around major competitions. Recently, someone commented that I was “too nice” and that I “brought unnecessary attention to myself” for congratulating a teammate who wasn’t even in my event. It’s this weird narrative where women in sport are either “too nice to be competitive” or “too competitive to be likeable.” Meanwhile, male sportsmanship is celebrated. Women online are often pitted against each other, subtly or explicitly. There’s an unspoken pressure to show up as feminine, pretty and unthreatening, while also being elite competitors. It’s a narrow, exhausting space to inhabit. A 2022 study by Women in Sport found that one in three female athletes had experienced abuse or trolling online, much of it rooted in gender bias. I love to show up online, but there’s definitely a big part of myself I hold back for fear of how I’ll be received.”

“I’m incredibly fortunate - in my sport, mental health is treated as a core part of performance. Sports psychology isn’t an afterthought; it’s embedded into how we train, how we prepare, and how we show up on race day. Psychologists are regularly available at camps and competitions, and we’re actively encouraged to work with them. One phrase that’s always stuck with me is: “human first, athlete second.” And that’s something we truly live by. If I’ve had a poor race or a tough session, I’m not immediately picked apart as an athlete; rather, I’m checked in on as a person. That emotional grounding makes all the difference. I think it’s really healthy to learn how to separate your self-worth from your performance. Sport is what we do, not who we are. And the better we are at recognising that, the longer and stronger we’ll last in this game.”

Emma Pooley, Team GB Olympic silver medal cyclist

Emma Pooley, Team GB Olympic silver medal cyclist and author of Oat to Joy

“When I was racing as a professional cyclist, I found the widespread obsession with weight very difficult. It's pervasive in the sport, at amateur and elite levels, where there was a lot of pressure to be skinny from team directors, selectors, and coaches. It was basically an accepted truth that skinnier is faster, and while weight is an important factor in performance, it's not as simple as "less weight is always better". Especially for sustainable health and performance.”

“It affected me to the extent that I developed an eating disorder, bulimia, and became generally very restrictive around my diet. It was a difficult time, trying to follow the "norm" while knowing deep down that it was harmful. In the end, what helped me was my love of food - I realised that the healthy, real food I ate - not sports products and refined junk - the faster I could ride. I also realised that the joyless attitude to diet in cycling is deeply unhealthy, and that the more I enjoyed my food, the happier and faster I was.”

“No support was given to me at the time. I was praised for losing weight, but if my performance suffered, usually due to under-fuelling or anxiety around performance, there was only criticism. I was never skinny enough that anyone realised I had a problem - I kept the secret well. But I think it's deeply hypocritical to encourage athletes to behave unhealthily, and not support them when they struggle due to that.”

“Personally, it’s too late to undo some of the long-term damage my body suffered from REDS (Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport), but there have been huge improvements in cycling. Most teams now have a better understanding of sports nutrition, women's health, and the warning signs of REDS. I know a lot of coaches and team directors are far better educated and more compassionate than some of the characters from when I was racing. But I do still worry about the smaller teams - it's still the case that many cyclists have to try to perform in a very unhealthy environment.”

“As a whole, cycling sets a bad example to viewers and fans, because a lot of elite riders are so thin. That's why so many leisure cyclists are also obsessed with losing weight - and as a goal, that's misleading, as well as sad. The best thing about cycling is taking joy in being active.”

Amber Keegan, Team GB Olympic swimmer

Amber Keegan, Team GB Olympic swimmer and founder of Athlete Interactions

“It’s hard - and busy - being an athlete and a person. Trying to train and manage your personal relationships, often at the same time as being a student or employee, is a lot.”

“Women’s sports are typically less well funded, which means women often work more jobs around a full-time training schedule and have less rest and recovery time, negatively impacting mental health. We’re also often in male-dominated environments, whether that’s training groups, coaching and support staff, which can often mean our specific needs aren’t understood.”

“While the gender pay gap is luckily small in my sport, there are other stressors that women have to face which men don’t. From childhood, expectations are placed on women’s bodies in a way that they aren’t for men. And as you progress to the elite level, women often suffer more abuse than men for just doing their jobs and performing to their best, which takes a mental health toll, too.”

“That said, the dial is definitely changing. Role models like Simone Biles and Mikaela Shiffrin have gained respect for being open and honest about their mental health. While they are widely celebrated for that, I don’t think they would have been five to ten years ago, which marks a clear positive change.”

“But more still needs to be done. Most clubs can’t offer the same level of support to individuals. Grassroots sport often struggles for funding. For those organisations that do have the funds to offer mental health support, athletes are (often rightly) concerned about the impact of what they say, whether it will impact team or funding decisions, and whether their honesty will have career ramifications.”

“We know that the sooner you get help, the faster a full recovery is possible. It’s more economically beneficial to get people the support they need. Sadly, the system is so backlogged that ASAP can look like months to years. This is a real issue, and one that’s relevant to all people.”

What needs to change to ensure female athletes get the support they need?

It’s a good question, and one that the expert I spoke to had a pretty resounding answer to.

Sarah Bellew is the Head of Communications at the Women In Sport charity, the longest-standing charity in its field with a proud history of securing change for women and girls. In her opinion, raising awareness of the issue is a good start. “Many high-profile sportswomen have spoken out about the immense pressure they face to perform in front of an often-critical crowd,” she shares. “Former Lioness goalkeeper and MC UK cover star Mary Earps has become an outspoken advocate for mental health, speaking candidly about how her struggles almost led her to quit her dream.”

While conversations are taking place and we’ve seen sports, like football, cricket, and gymnastics review their player conditions, coaching practices and wider culture to ensure the mental and physical health of women and girls is protected, there’s still so much more to do. “Statistics show that one in three female athletes feel they don’t get enough coaching support compared to men, and three in four say they’ve experienced sexism in their sport,” she continues. “The dial is shifting, but until women and girls are seen as equal to men and boys in society, they will not be seen as equal in sport, and the barriers stacked against them will continue to weigh them down.”

She’s all for pioneering innovations, such as using AI to monitor and block harmful social media comments. “World Athletics, which found female athletes at the Paris 2024 Olympics were being targeted with sexual and sexist abuse, is now offering year-round protection to 25 athletes who have been identified as highly-targeted individuals,” Bellew shares.

That said, she reflects that while this may prevent some comments from getting through, it doesn’t go far enough in creating repercussions for the users who are actively promoting sexism. “Social media giants must work harder to block these accounts and prove that misogyny, or any other form of abuse, will not be tolerated – in sport, or anywhere,” she shares.

While social media firms must be held to account, it’s also worth thinking about how we tackle the root causes of these issues. At Women in Sport, they’re calling on the Government to introduce a standalone legislation that criminalises misogyny as, astoundingly, it’s not currently recognised as a hate crime.

Bellew’s final thoughts? “Female athletes at the top of their sport have had to develop exceptional resilience, achieving greatness despite coming up against the glass ceiling again and again. But can you imagine what they might be able to achieve if they didn’t have to worry about being criticised for the way they look, the way they play and for simply existing in a space that wasn’t made for them?,” she asks. Until sport understands the lived realities of women, not just physically but socially and psychologically, we will keep losing talent, joy and brilliance from sport, she concludes.

Ally is Marie Claire UK's Senior Health and Sustainability Editor, a well-regarded wellness expert, ten-time marathoner, and Boston Qualifying runner.

Utilising her impressive skillset and exceptional quality of writing, she pens investigative, review and first-person pieces that consistently demonstrate flair and originality.

As well as writing, Ally manages a team of freelancers, oversees all commissioning and strategy for her pillars, and spearheads the brand's annual Women in Sport covers, interviewing and shooting the likes of Mary Earps, Millie Bright, and Ilona Maher. Shortlisted for three BSMEs and winning one in 2022, Ally lives and breathes her verticals: her eye for a story and connections within the wellness sphere are unrivalled. Follow Ally on Instagram for more.