How Nelson Mandela's Story Defined A Generation

For anyone my age, Nelson Mandela's life story and his politics runs in our blood, says Miranda McMinn, Marie Claire's Associate Editor.

For anyone my age, Nelson Mandela's life story and his politics runs in our blood, says Miranda McMinn, Marie Claire's Associate Editor.

Nelson Mandela is a name I have known as long as I could talk. My parents were both South African-born, and left the country when I was a baby, unable to square their consciences with living under apartheid for a moment longer. The apartheid regime insisted on segregating people according to their skin colour; black and "coloured" people did not have the right to vote; they had to carry passes and if they failed to do so were imprisoned and maltreated; thriving communities were bulldozed and their property taken; protesters were arrested, beated, tortured, imprisoned. It was the late 1960s and Mandela had already been in prison since 1962. My grandparents had moved back to their native Holland a couple of years earlier – my grandpa had fought the Nazis and had said he couldn’t stay around to see it all happening again.

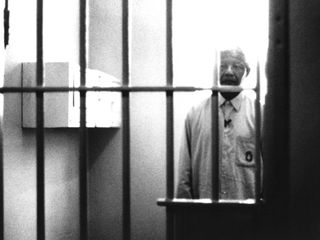

As a child I knew all about Robben Island, the prison where Mandela was moved in 1964. There were lots of (mostly white) South Africans in London. Many of them were “banned” from the country for political activity. Some had been in prison too. But my mum was very candid about the fate that had befallen their black counterparts who had been less fortunate, unable to leave the country that was undergoing this evil social experiment. They had been imprisoned for life, tortured by having electrodes attached to their genitals, beaten to death in police cells. I can feel my eight year old self wincing at this information, and later looking on as my mother shouted at the radio after the police opened fire on the Soweto uprising in 1976, killing hundreds of high school students who were protesting. “They’re just children!” she bellowed, angrier than I’d ever seen her.

Nelson Mandela and South Africa defined my teens too. Magaret Thatcher called his organisation, the ANC, "terrorist" and refused to back sanctions - it was another reason to hate her. “Free Nelson Mandela” by The Specials AKA got to number nine in 1984. In politically correct circles you were not allowed to eat Cape grapes or drink South African wine. I knew that South Africans didn’t have television (unthinkable elsewhere in the world). There was little point, because the global boycott meant that they would have had nothing to put on it. They could take part in no sports either. And then, in 1989, everything changed. The Berlin wall came down, and most joyous of all, in early 1990, Nelson Mandela was released.

The feelgood factor generated by this one event was enough to carry us all buoyantly for at least a decade. To cap it all, with his policy of Truth and Reconciliation – rather than the call for revenge which would have been so understandable and so devastating – he set us all the ultimate example. Be the bigger person. Of course he did this for political ends. If you read his book you realize that more than anything this is what he was, what he stood for: the political fight against a system so brutalized and cruel and unfair. But it was a lesson for all of us about the effectiveness of such a stand.

None of my family had ever been back to South Africa while he was imprisoned, but suddenly it was OK. So finally in 1999 I visited the country where I had been born. I took the day trip out to Robben Island. Our guide was a former political prisoner. He showed us where Nelson Mandela had been made to break rocks in the sun, and described how particularly sadistic guards had buried prisoners to their necks in the dirt before urinating on their heads.

I stood in the tiny cell where Mandela had been confined for decades, with all the memories of the man and what he represented ringing in my ears, and burst into almost uncontrollable tears – of sorrow and anger, and of guilt for being white (an emotion shared by many South Africans, I think, if they are being honest). A black woman, also on the day trip, saw me and put her hand on my arm. In that familiar accent she said to me, “We must be strong.” It’s what South Africans will have to be now.

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Take a look back at Nelson Mandela's life in 100 amazing photos

-

Joe Alwyn secretly co-wrote six Taylor Swift songs and we had no idea

Joe Alwyn secretly co-wrote six Taylor Swift songs and we had no ideaBy Jenny Proudfoot

-

I’m calling it, these 8 honey fragrances are the elevated gourmand scents everyone will be spritzing this summer

I’m calling it, these 8 honey fragrances are the elevated gourmand scents everyone will be spritzing this summerSweet yet sophisticated

By Jazzria Harris

-

These are the 10 best core activations you can do to fire up your abs, according to top PTs

These are the 10 best core activations you can do to fire up your abs, according to top PTsNot a crunch in sight.

By Anna Bartter