Life Stories: Björk

Ahead of her headlining gig at Wilderness Festival this weekend, we revisit Björk's life story...

Ahead of her headlining gig at Wilderness Festival this weekend, we revisit Björk's life story...

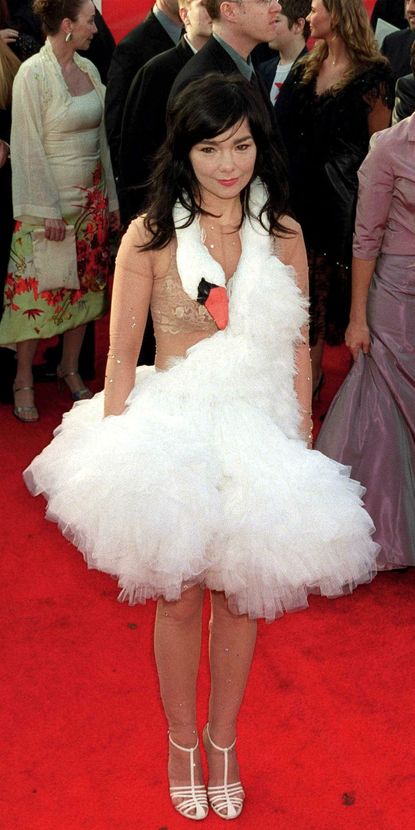

Pioneer, activist, brilliant bonkers powerhouse – she may have a 50th birthday on the horizon, but as her mesmerizing new album proves, the Icelandic musician is still a creative force to be reckoned with. It’s red-carpet time at the 2001 Oscars and, amid a tasteful tide of actresses in the usual designer gowns, there is Björk, nominated for Best Song for the film Dancer in the Dark, in which she also stars. She’s wearing a feathered dress that looks like a swan – its head draped around her neck and every few steps she lays an ‘egg’, prompting security guards to say solicitiously, ‘Excuse me, ma’am. You’ve dropped something.’ This is the kooky Björk commentators and comedians love – the cute Icelander raised on a commune; the child-woman with the breathless vocals whose song It’s Oh So Quiet was reportedly used by the CIA to extract confessions. But that’s to devalue the work of this multi-talented artist and activist who’s currently the subject of a major retrospective at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Klaus Biesenbach, the curator of that exhibition, describes her as ‘aggressively vulnerable, bold and fragile, wild and sensitive, little girl and femme fatale. She is the melancholic, suffering dancer in the dark and at the same time the “violently happy” character.’ She’s been the victim of a bomb plot (sent by a suicidal fan), casual sexiam (‘It’s tough. Everything a guy says once, you have to say five times’) and heartbreak (her latest album chronicles her split from artist Matthew Barney), but she has also sold more than 20 million albums worldwide, won numerous awards and was the first artist to release a record as a series of interactive apps, as well as the more conventional formats. Dressing up as a swan is just par for the course…

Björk Guomundsdottir was born in Reykjavik in November 1965. Her father, Guomundur Gunnarsson, was a union leader and electrician. Her mother, Hildur Hauksdottir, was a ‘dreamer’ who left with Björk a year after her daughter’s birth to live in a commune. ‘It wasn’t like I was brought up by wolves,’ Björk has said. ‘But it was very much a question of getting a key around my neck and becoming my own little trooper.’ She began music school at six and released her first album – a collection of covers and Icelandic songs – when she was 12. Bjorgvin Gislason, who played guitar on the record, remembers, ‘She was quite different from other kids – she knew what she was going.’ When the record company asked her to make a follow-up a year later, she refused. Even then, she knew she wanted to make her own music.

Björk left school at 15 and discovered punk. Iceland has a population of just 325,000 and Reykjavik is a city where everyone knows each other. Over the next few years, she lived and performed with a loose collective of friends, forming bands with names like Spit And Snot and Tappi Tikarrass (translation: ‘Cork the Bitch’s Ass’). When she fell in love with fellow musician Thor Eldon at age 16 and had a son, Sindri, four years later, in 1986, it didn’t stop her from getting up on stage and performing – an old lady reputedly had a heart attack after watching a pregnant Björk, bare belly writhing, singing on an Icelandic show. But Björk was always destined for more than local infamy. That same year, despite getting a divorce, she and Eldon formed the Sugarcubes, whose first single in English, Birthday, became an international sensation. One day they were playing in tiny clubs in Iceland; the next they had NME's Single of the Week and were touring America, the subject of a record-company bidding war. This was the start of the Björk myth, with bewitched pop writers describing her as a pixie leading a band of eccentric elves. Looking bar, fellow Sugarcubes member Einar Om Benediktsson says, ‘I do not understand that idea of otherness and oddness, as we are very normal. We know how to dress ourselves and brush our teeth and eat. But the challenge is to not take no as an answer. To explore and be awakre. The boundaries are there to be broken.’ Björk’s boundary-breaking included taking her young son on tour, but already she was outgrowing the Sugarcubes. The band split in 1992. Björk moved to London with Sindri to make a new start.

It was the era of raves, beats and the throb of dance music. Björk embraced it all, melding her classical training, love of jazz and incredible voice with a passion for electronica. For her, making music was instinctive and sensual, ‘almost like you had sex lots of times and it’s gorgeous,’ she said. At the same time, she was exploring her image, working with fashion designers including Alexander McQueen and Hussein Chalayan, and photographers Juergen Teller and Nick Knight. Like Madonna, she released best-selling records throughout the 1990s, but the looks she created for her songs couldn’t have been more different to the Material Girl’s hyper-sexualised image. ‘Some of her work has been erotically explicit: the music video for Pagan Poetry shows Björk semi-naked with beads swen into her skin. But her work makes an unusual alliance between a woman’s sexual identity and motherhood,’ says Nicola Dibben, a professor of musicology who has contributed to Björk: Archives (Thames and Hudson, £40). At the same time, Björk was talent-spotting movie-makers – as well as Spike Jonze, created of Her and Being John Malkovich, she’s made videos with Michel Gondry, who went on to film Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind with Kate Winslet. ‘She’s very sensitive to the human condition. She can take a simple, everyday element and find the magic in that,’ Gondry says.

Björk’s collaborations with musicians often led to romantic entanglements, although, as journalist Lynn Barber once commented, falling in love isn’t Björk’s problem; staying in love is. Her affair with drum and bass artist Tricky seemed doomed from the start. ‘There was someone else in the background, an ex and a child, and all sorts of complications. I just said to her, “Don’t get hurt,”’ explains Björk’s friend Netty Walker. Tricky had his own reservations, recalling, ‘The first time I met her, I thought, “There’s a vibe between us. Nah, forget about it because it ain’t a good thing.”’ Their relationship imploded under the pressure of private emotional baggage and media publicity. Not long after, Björk fell for Goldie, another drum and bass musician. ‘It should have been the perfect scenario: this girl wants to marry you, wants you to come and live in this big fucking house. And I said no,’ Goldie confesses. ‘Something in me said, “You’re not to be in love until you’re happy with yourself.” No one could help me but me. She got a broken heart over it. She was sad.’

It was 1996 and, after the soaring success of her solo career, Björk entered a dark time. Earlier that year, she attacked a TV reporter who tried to question 10-year-old Sindri as they arrived at Bangkok Airport. “I suddenly aw her on the floor with someone,” recalls band member Leila Arab. “My instict was, ‘shit someone’s jumped her,’ and it’s like, ‘No, it’s crazy Björk.’” The next year, a disturbed fan, Ricardo Lopez, posted an acid bomb to her, then filmed himself as put a gun in his mouth and fired. The bomb was intercepted but Björk was devastated. “I cried for him and I was very upset over his death,” she said, even sending flowers to his family. “But for me, it destroyed my home. I had to rediscover everything.”

Marie Claire Newsletter

Celebrity news, beauty, fashion advice, and fascinating features, delivered straight to your inbox!

Throughout 1999, she threw himself into recording the soundtrack and starring in Lars Von Trier’s harrowing film Dancer in the Dark, playing a woman losing her sight. The shoot has gone down in film history for the clashes between director and star. He is infamously uncompromising and has been accused of brutalising actress; Björk is similarly inflexible about her musical vision and wouldn’t back down to his demands. In the book Björk: Wow and Flutter, the film’s producer Vibeke Windelov claims Björk broke down over her costume for the part. “She’s biting the blouse and throwing pieces on the ground. And she’s really fast, really furious – biting and throwing, biting and throwing. Then we get to a fence and she crawls up it – it’s two or three metres tall. She goes over it, throws the blouse to me, jumps down on the other side.” Björk claimed the experience left her so scarred she’d never act again. Even so, she won Best Actress at the 2000 Cannes film festival.

Björk’s retreat back to music marked a renaissance in her work and a resolution, for a time, in her love life. In 2000 she met American multimedia artist Matthew Barney, and her album Vespertine, released a year later, is a love song to him. The couple had a daughter Isadora, in 2002, and divided their time between New York and Björk’s house in Reykjavik. Easy domesticity was never going to be an option for such a creative couple, however. Although fiercely private, they collaborated on an art film that ended with them flaying each other with knives before diving into the sea and turning into whales (the reviews ranged from ‘brilliant’ and ‘beautiful’ to ‘pretentious art nonsense). Björks’ solo work was just as controversial, but critically and commercially successful. In 2011, she release Biophilia – a groundbreaking album inspired by her passion for nature (and David Attenborough: 'I have learned so incredibly many things from him,' she says). No one would provide funding for such an experimental project, so Björk went back to how her music started. 'Everyone works for free, then we split the profits by 50/50. This is how we did it back in the punk days. That was amazing on so many levels,' she said. Biophilia workshops for children were held worldwide and the apps because part of the school curriculum in Reykjavik, a far cry from Björk’s childhood in education, when she would tell the principal how to run his music school 'because they want t make a conveyor belt for symphony orchestra.'

She was challenging the system in other ways, too. As well as proclaiming her support for Russian punk activists Pussy Riot, Björk protested against the Icelandic government’s plan to build five polluting aluminum factories in the country’s pristine landscape, and put up a petition asking that the country’s energy resources should be kept in public ownership – incredibly 25 per cent of the voting population followed her lead and signed. As Einar Orn Benediktsson says, 'She is still regarded as one of us.'

In 2013, Björk and Barney split up; 'It all just collapsed. I didn’t have anything,' she says. She’s poured her heartbreak into her newest album Vulnicura which was released to coincide with the MoMa exhibition. It’s the ultimate break-up album, with tracks charting a timeline from nine months before to 11 months after the end of their relationship. Announcing the album on Facebook, Björk wrote: 'Hopefully the songs could be a help, a crutch to others, and prove how biological this process is: the wound and the healing of the wound, psychologically and physically.' The final song on the album proclaims, 'When we’re broken we are whole and we’re whole we’re broken.'As Björk’s wounds heal, the world waits to see what she does next.

Words by Andrea Childs.

The leading destination for fashion, beauty, shopping and finger-on-the-pulse views on the latest issues. Marie Claire's travel content helps you delight in discovering new destinations around the globe, offering a unique – and sometimes unchartered – travel experience. From new hotel openings to the destinations tipped to take over our travel calendars, this iconic name has it covered.

-

I just sat down with a celebrity tan expert and he told me that these are the only tanning tools you need for a streak-free glow

I just sat down with a celebrity tan expert and he told me that these are the only tanning tools you need for a streak-free glowYour ultimate at-home tan kit

By Mica Ricketts

-

Anne Hathaway had to kiss 10 men during a 'gross' chemistry audition early in her career

Anne Hathaway had to kiss 10 men during a 'gross' chemistry audition early in her careerUgh

By Iris Goldsztajn

-

There was a hidden code in Baby Reindeer that everyone completely missed

There was a hidden code in Baby Reindeer that everyone completely missedDid you spot it?

By Jadie Troy-Pryde